November 16, 2018

Asia Needs Pence’s Reassurance

By Patrick M. Cronin

He should confront Trump’s mistakes and put forward a positive agenda.

In Asia, anxieties about the United States’ role in an increasingly China-centered world are palpable. While some fear that the United States is retreating from its international obligations, other worry that it is bent on instigating conflict.

.As U.S. Vice President Mike Pence visits Southeast Asia and the South Pacific this week to attend the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation leaders’ meetings, he should make clear that the United States remains a stalwart partner for the region with a vision for peaceful cooperation and development.

No U.S. retreat

The United States is not withdrawing into fortress America. It remains actively engaged in global affairs and is focused on strengthening the economic and military foundations of its power. The country’s central aim is to stay competitive in a world driven by a dynamic Indo-Asia-Pacific region. That goal, of course, derives from a real concern that China is challenging the postwar order and an understanding that the United States needs to find new ways to renew its diplomatic, economic, and military competitiveness.

The United States is not withdrawing into fortress America. It remains actively engaged in global affairs and is focused on strengthening the economic and military foundations of its power. The country’s central aim is to stay competitive in a world driven by a dynamic Indo-Asia-Pacific region. That goal, of course, derives from a real concern that China is challenging the postwar order and an understanding that the United States needs to find new ways to renew its diplomatic, economic, and military competitiveness.

But as U.S. President Donald Trump said last November in Da Nang, Vietnam, the United States has been “an active partner in this region since we first won independence ourselves,” and “we will be friends, partners, and allies for a long time to come.” U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has likewise been a forceful advocate for diplomacy in the region. Meanwhile, Congress is on the cusp of passing a bipartisan bill designed to bolster U.S. engagement there. The Asia Reassurance Initiative Act would authorize $1.5 billion in new funding over the next five years for regional diplomacy, development, and defense programs. In short, rumors of America’s disengagement miss the mark.

No Cold War with China

Pence also needs to reassure the region that when it comes to China, the United States is not seeking a war—trade, cold, or hot.

Pence also needs to reassure the region that when it comes to China, the United States is not seeking a war—trade, cold, or hot.

Instead, the U.S. administration wants a fair, open, and cooperative relationship. That doesn’t mean ignoring China’s attempts to compete with the United States, including through grey-zone operations like muscling the Philippines out of Scarborough Shoal and militarizing artificial islands despite pledging not to do so. And America will not shy away from meeting challenges directly. But on a fundamental level, the Trump administration would like to channel competition toward cooperation where possible.

In fact, the Trump administration rejects the idea of Thucydides’s Trap: that conflict between a rising power and a status quo power is inevitable. Leaders have agency, and it is up to them to determine the future course of relations. And for its part, the United States seeks to remain a force for good, not to contain or curb the China’s peaceful rise.

Of course, it would be useful for Pence to clarify that Washington will not tolerate coercion or the use of force against allies and partners in the region. But the vice president should also reiterate what he said last month at the Hudson Institute: “America is reaching out our hand to China. We hope that Beijing will soon reach back with deeds, not words.” That sentiment is broadly shared, even among Democrats, who do not agree with some of the administration’s tactics. (As Joaquin Castro, a Democratic representative from Texas, said last month, China should “compete, not cheat.”)

US Vice President Mike Pence has confronted Myanmar’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi at the ASEAN summit about what is being done to hold those responsible for the persecution of the Rohingya ethnic minority in her country to to account.

This will be a difficult balance to strike. And here, China’s approach to the South China Sea is instructive. It alone pursues claims there based in part on historical rights rather than contemporary international law. It showers the region with promises of infrastructure investment, but it fails to deliver transparent, equitably financed, high-quality development. It promises to follow an ASEAN Code of Conduct for the region but seeks a veto on the right of ASEAN members to extract natural resources from the South China Sea or hold military exercises there with Australia, Japan, the United States, and other non-ASEAN states.

But the fear that a major confrontation, or even war, will play out in Southeast Asia is greatly exaggerated. China seeks to advance its goals by means short of war, and the United States aims to cooperate where it can but compete where it must. The resumption of the Diplomatic and Security Dialogue—a U.S.-China working group involving top defense and diplomacy officials—is thus a good sign.

Yes to an affirmative agenda for Asia

Beyond dispelling myths about U.S. retrenchment and bellicosity, Pence should also put forward a positive agenda for Asia. Here, he will have to confront some of Trump administration’s mistakes.

Many in the region question the United States’ predictability, because Trump has reversed major U.S. initiatives, from the Trans-Pacific Partnership to the Paris Agreement on climate change. Meanwhile, he has escalated tariff wars without articulating a coherent strategy for achieving results, and his uneven application of penalties has rankled allies and competitors alike. Nor has the administration deployed soft power well, often ignoring U.S. values like democracy and human rights, turning the country’s back on refugees, using unbefitting language, papering over conflicts of interest rather than cracking down hard on corruption, and being far too comfortable with authoritarians.

Despite these missteps, Pence can use the trip to Asia to burnish four cornerstones that should be the foundation of the administration’s free and open Indo-Asia-Pacific strategy, especially in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Those four elements are a rules-based order, sustainable economic development, inclusive diplomacy, and effective security cooperation.

First, upholding and peacefully adapting the set of rules chosen freely by strong and independent sovereign states will be the foundation for U.S. engagement with the region. The United States has enduring interests in the South China Sea: stability, freedom of navigation, and resolving disputes peacefully and without coercion.

Although ensuring the rule of law will require far more than freedom of navigation operations, the United States will continue to help maintain the openness of the seas by sailing, flying, and operating anywhere international law permits. Importantly, seafaring nations from Asia and Europe are also demonstrating their commitment to the same cause by conducting similar operations.

Second, for growth to be sustainable, it has to be fair and reciprocal. It should be pursued in a manner that is transparent, non coercive, and environmentally sustainable, especially when it comes to the global maritime commons. There is nothing wrong with China’s Belt and Road Initiative that sunshine and high standards of accountability cannot fix.

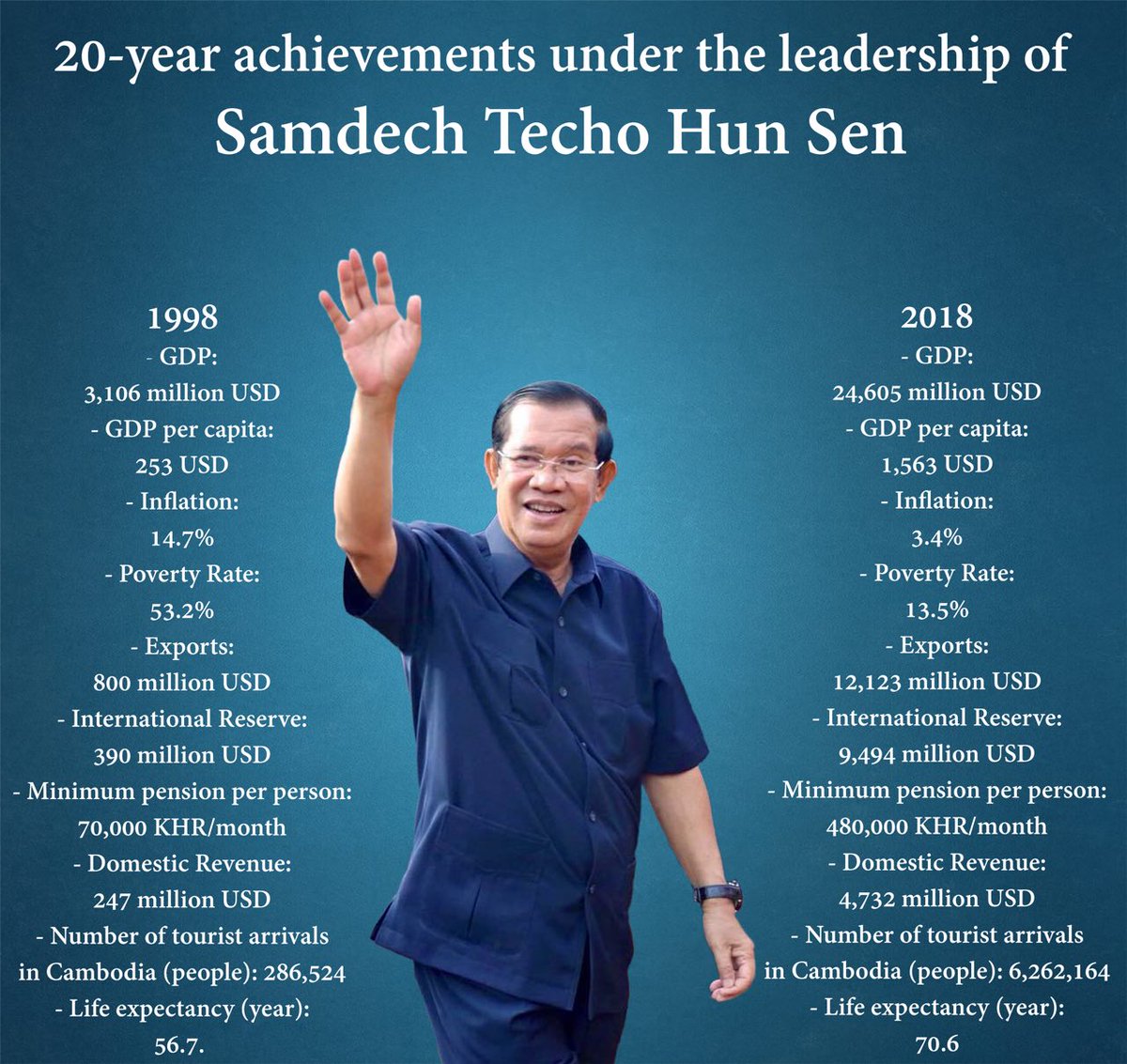

Meanwhile, the United States should go even further to mobilize public and private support for trade, investment, and development. Eventually, the country can create a whole constellation of allies and partners that can invest in energy infrastructure, digital connectivity, transportation, and more. For instance, the United States is in active discussions to leverage the BUILD Act to expand joint efforts with allies and partners in the Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and elsewhere. In doing so, it can set a gold standard for development in the region.

Take Indonesia for example. China aside, a prosperous, democratic, and stable Indonesia is in the vital interest of the United States. Yet few in Washington are aware of the opportunities that await in Southeast Asia’s most populous country. The U.S. government’s Millennium Challenge Corporation has just completed a successful economic investment in Indonesia. Pence should ensure Washington starts negotiating a follow-on compact while simultaneously using BUILD Act funds to facilitate new U.S. private sector entry into Indonesia.

A third tenet of U.S. policy in Southeast Asia is inclusive diplomacy, including trust-building with competitors and partners alike.

ASEAN deserves broad support for its unique convening authority. Certainly, that is a major reason why the United States embraces the body having a loud unified voice in Indo-Pacific engagement. It also is in favor a strong, binding Code of Conduct—not one that unfairly limits the freedom of action of Southeast Asian states.

Inclusive confidence-building measures, such as plans to extend the voluntary Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea to include coast guard vessels and efforts to protect rapidly depleted fishery stocks, deserve action. The United States should signal its support for promoting a new framework of “Resilience, Response, Recovery,” which is one of several useful concepts being put forward by ASEAN under Singapore’s chairmanship. At the same time, ASEAN members are pragmatic. The United States will often have to cooperate with them on a bilateral or trilateral basis to find effective responses to real challenges.

In terms of diplomacy with China, it might be worth creating a new crisis avoidance mechanism—perhaps mirroring the 1972 Incidents at Sea agreement. The bilateral pact did not prevent all U.S.-Soviet mishaps, but it helped avert major disasters, something that is even more important in a region where intermediate-range cruise missiles, hypersonic weapons, and the military use of cyberspace and outer space are unrestricted.

Finally, the United States will continue to support effective security cooperation centered on information sharing, capacity building, and interoperability. The United States should buttress such efforts by firming up its commitment to respond appropriately to threats of coercion and the use of force.

Boosting the ability of allies and partners to see better what is happening in their maritime backyards will help them become more resilient. And assistance with capacity building, especially for coast guards and other law enforcement agencies, will give nations a better ability to protect their sovereignty. Bilateral, “minilateral,” and larger multilateral exercises can also help create a readiness for dealing with future contingencies.

In sum, a confident but not boastful United States is neither stepping away from Asia nor trying to provoke wars there. Rather, it aims to ensure stability in the region so that all countries there can advance both sovereign interests and regional cooperation.

Patrick M. Cronin is senior director of the Asia-Pacific Security Program at the Center for a New American Security in Washington.

@PMCroninCNAS

china/#39;s%20Picks%20OC