March 28,2019

10 unlikeable things about Dr M

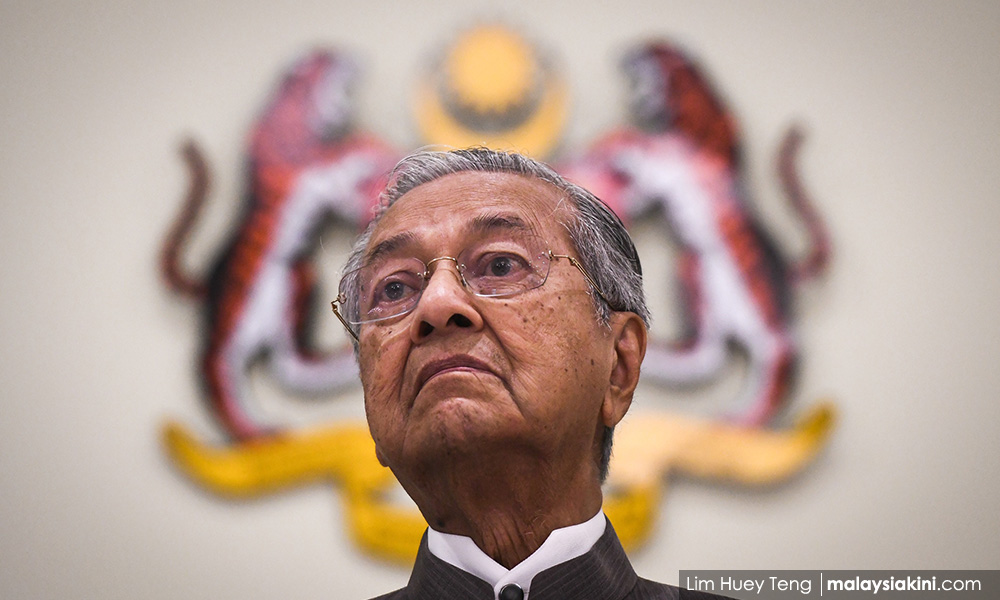

QUESTION TIME | Nurul Izzah Anwar’s misgivings about Mahathir, aired in an interview she gave to Singapore’s Straits Times, has been both condemned and praised for calling Dr Mahathir Mohamad a former dictator and a person who is very difficult to work with.

Unfortunately, less attention has been given to some of the reasons for her dissatisfaction, which is of greater importance to what is happening in our country. As she further said in the interview the government, led by Mahathir, has not done enough to embolden moderates.

Here’s an extract from the report in Malaysiakini: “We’re not doing enough to embolden the middle. We’re not doing enough to embolden those who are considered moderate,” she was quoted as saying.

The former PKR vice-president also admitted to being dismayed by how UMNO lawmakers are being courted to join Harapan over the last several months.

“It’s a horrible predicament, not just for Keadilan, (but) for Malaysia, for their voters, for our voters, for Malaysians as a whole.

“It’s just a sad state of affairs because I believe a two-coalition system is important for the future of Malaysia,” she lamented.

That hits out at the fundamental problem which is facing the ruling coalition. It really is not about gaining Malay support, but Mahathir boosting his own power within the coalition by swelling the numbers of Bersatu MPs through defectors. Bersatu has doubled its number of MPs to 26 from such defections. And it’s about what kind of reform should take place.

There is a lot not to like about Mahathir if we go back in history and he is everything and more what Nurul said he is. He changed the constitution and laws to become a virtual dictator both within Umno and the country, and paved the way for Najib Razak to abuse his powers to approve and condone the largest kleptocracy the world has seen.

The important question is how much is Mahathir a changed man post GE14? Here are 10 unlikeable things about Mahathir and what his fervent supporters say about him.

1. Without Mahathir, the elections would not have been won.

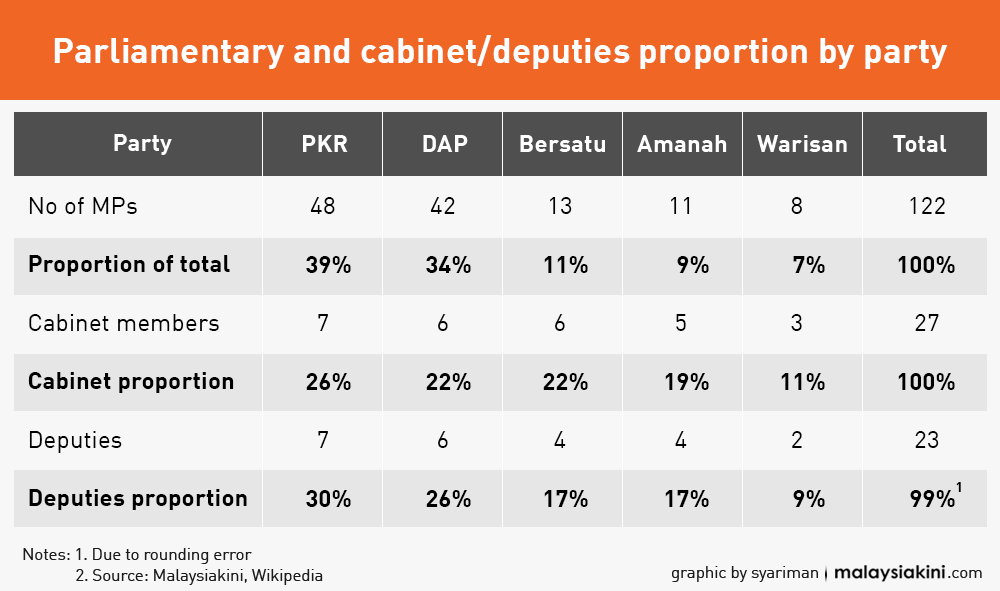

This is a rather ridiculous statement to make by his supporters. Would the elections have been won without PKR or DAP? Certainly not. The numbers indicate that without a doubt, with PKR having won a total of 47 seats, and DAP 42. Mahathir’s Pribumi won only 13 seats, while Amanah took 11.

PKR and DAP’s parliamentary seats win rate for Peninsular Malaysia was over 80 percent and 90 percent respectively. Amanah’s was 35 percent, but Bersatu’s was a mere 25 percent, despite the largest number of seats contested in the peninsula of 52. I have explained this in much greater detail here.

2. Mahathir came up with a rather lopsided cabinet.

Despite just having 13 parliamentary seats, Mahathir abandoned consensus, which the coalition had advocated, in favour of prime ministerial prerogative to give his party Bersatu – a right-wing Malay party – a disproportionate number of key seats in the cabinet.

Such was Mahathir’s patently unfair cabinet that out of the 13 MPs he had, six became full ministers, a further six deputy ministers, and one, Mahathir’s son, became menteri besar of Kedah. Four of the Bersatu ministers were first-time MPs, including a boy MP and minister, clearly ignoring those who had fought long and hard in PKR and DAP. I have dealt with this in detail here.

3. He deliberately caused schisms within the coalition.

By appointing Lim Guan Eng as finance minister without consultation and consensus within Harapan, he almost derailed the coalition in its first few days when there was a protest walkout by PKR leaders. The tense situation was only alleviated later after PKR and Harapan de facto leader Anwar Ibrahim intervened.

The DAP was elated with Lim’s appointment, and frequently cited prime ministerial prerogative in the early days when Mahathir had appointed just 10 key people to the cabinet. When Mahathir ignored his own promise to ensure ministerial composition reflects parliamentary representation, even the DAP was disappointed. (see table).

The other thing he did was to appoint PKR deputy president Azmin Ali as economic affairs minister when his name was not even in the list of PKR nominations because he was menteri besar of Selangor at the time. The more prescient among us saw that as a move to position Azmin as a possible successor to Mahathir, and to drive a wedge between Azmin and Anwar. It has worked very well.

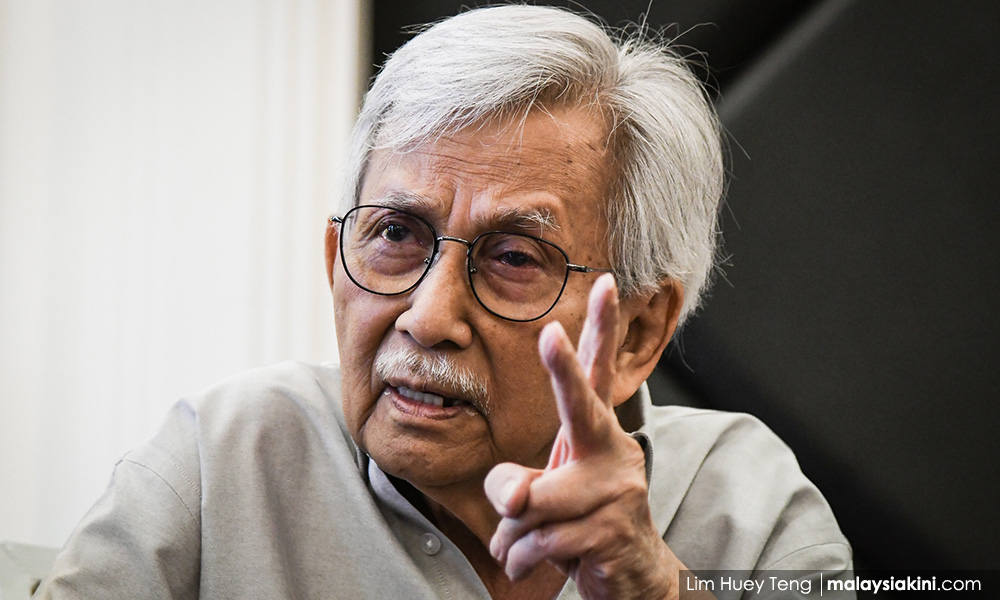

4. He brought in Daim, undermining the cabinet.

It is an open secret that Daim (above) and Anwar don’t get along, and that Daim has a finger in many economic and business pies. Thus, to appoint him the chairperson of the so-called Council of Eminent Persons (CEP) and to put him overall in charge of producing a blueprint for Malaysia Baru was a slap in the face of the new government which had reform in its mind.

Daim, despite all the unease that people have expressed to Mahathir about him and have written about in the media, still holds considerable power and is the lead negotiator with China, a country that undermined Malaysia by doing corrupt deals with Najib’s administration. He is also said to be in charge of 1MDB investigations and why this should be so is unclear.

Daim being put above the cabinet and reporting directly only to Mahathir, raises key questions as to how transparent the new government is and possible conflicts of interest because of his ties to business and his closeness with many businessmen.

5. Mahathir has not done anything about legal reform.

During his tenure, Najib introduced a whole slew of new laws to increase his hold on the country. These laws can easily be overturned pending a more holistic review of the legal system to put in checks and balances for the executive branch, but Mahathir has not moved at all on this. Instead, he said that the Official Secrets Act (OSA), which he tightened during his previous tenure to provide for mandatory jail sentences, will remain.

Then he rather ridiculously stated that many promises made in the Harapan manifesto cannot be implemented because Harapan did not expect to win the elections.

Some promises such as eliminating tolls may need to be dropped because of under-estimation of costs. But this is not the case for changing laws, which can be done by a simple majority. There is no need for a two-thirds majority to amend many of these laws.

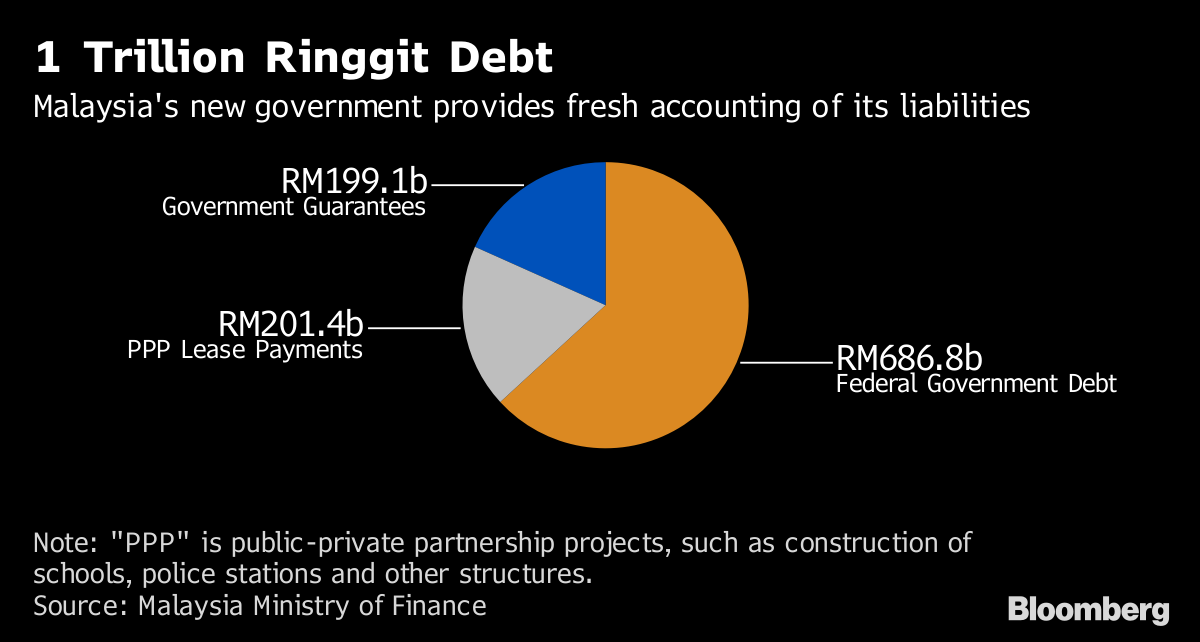

6. He perpetuates the lie that the national debt is RM1 trillion.

He perpetuates the lie that the national debt is over RM1 trillion, first stated by finance minister Lim as an excuse for not fulfilling some promises.

While the national debt position may not be in the best possible situation, it is wrong to say the debt is RM1 trillion, as I explained here. It is so only after taking into account contingent liabilities, guarantees and lease payments. Not all contingent liabilities or guarantees became debt. And lease payments are not necessarily debt. Certainly not in terms of internationally accepted debt classifications.

7. He is reviving his pet failed projects and concepts.

After his Proton national car project failed spectacularly, requiring several rescues and resulted in losses to the public in terms of excess prices paid for cars of hundreds of billions of ringgit, Mahathir is still foolishly adamant about a third national car project.

The car industry is already being shaken up and mergers have taken place. The much bigger companies make it impossible for a new Malaysian car project to succeed. This is irrationality of the highest order.

Then he talks about privatisation again, when during his time the government gave up plum operations to connected businessmen, making them overnight billionaires. They include toll roads and the independent power producers amongst others.

8. He has shamefacedly accepted defectors into Bersatu.

Mahathir blithely talks about getting a two-thirds majority to change the constitution, but he has done nothing yet in terms of reform. That’s an excuse to just increase the pathetic number of MPs Bersatu has by pilfering other parties’ MPs. This is against the express wishes of the two largest parties in Harapan – PKR and DAP.

That these defections can happen now is because Mahathir, in his previous role as PM, changed laws and the constitution to make it legal for defections to happen, luring MPs into the ruling government to topple democratically elected state governments. He is doing the same now, not for any national interest, but to widen his narrow power base by dastardly means.

9. His government does not have a comprehensive plan and action programme.

Some 10 months after taking power, there is no plan on the table for the overall development of the country and to solve the various problems facing it. For the first few months, it was up to Daim and the CEP to come up with it. This has been submitted to the PM, but not made public. So no one, but a few, knows what they are.

Now, after the CEP, an economic council is being formed to formulate policy. What’s the point of the ministries then? Shouldn’t all of them have their own plans for the areas they supervise and should they not put it up before the cabinet and seek their approval?

10. He has not taken steps to be inclusive.

While Harapan campaigned on the promise of inclusiveness of all Malaysians in development and a needs-based approach to the assistance of deprived groups, Mahathir plays to the Malay gallery by talking about the Malay agenda, plans to distribute wealth among the races, and hiving off business activities to bumiputeras. Azmin echoes him, producing the schism between races that Harapan had promised to eliminate.

On top of that Mahathir equated the injuries sustained by a fireman at the Seafield riots to “attempted murder,” adding oil to an already incendiary situation, to appease the Malay gallery and vilify Indians without first properly ascertaining the facts.

All these are a reflection of Mahathir wanting to go back to the old status quo under a different name of Malaysia Baru. It’s about Malay supremacy and Mahathir is a Malay supremacist. It is very obvious at this stage that Mahathir is not the prime minister to reform this country. Someone else has to.

At the end of the day, this is what Nurul Izzah’s concerns are about. We should not be too concerned about where she said it or if she should not have said some things. We must look at the substance of what she said, and there can be no doubt that her concerns are justified.

Harapan should do something or lose its soul.

P GUNASEGARAM says dictators, even former ones, don’t easily take to reforms. E-mail: t.p.guna@gmail.com.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of