December 26, 2018

Harapan entering a grey area, a year before 2020

Opinion | by Phar Kim Beng

COMMENT | As I write this, Malaysia, as governed by Pakatan Harapan, is entering both a festive occasion – marked by Christmas and the New Year – and a festering one too. There are five telltale signs of the latter:

- The tragic death of firefighter Muhammad Adib Mohd Kassim in the Seafield temple riots.

- The 55,000 who gathered in Kuala Lumpur for the rally against the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Icerd).

- Authorities seemingly forgetting about M Indira Gandhi’s missing daughter, and about Teoh Beng Hock’s death nearly ten years ago.

- Close to 15 percent of Malaysia’ population will be above 60 years of age by 2023.

- About 38,000 Felda settlers getting cost of living aid and deposits for replanting.

In any one of the above, Harapan has at best either been silent, or belatedly proactive. Meanwhile, the world continues to change in five ways:

- US President Donald Trump deciding on two simultaneous withdrawals from Syria and Afghanistan, signalling the end of American presence in two of the most conflict-prone regions in the world.

- Russia staying quiet on the pullout of American troops, although this strategic withdrawal is akin to the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

- Islamic State and the Taliban also staying quiet, suggesting a deeper motivation to push deeper into the Western world, or perhaps Asia, to wreak more havoc;

- China’s One Belt, One Road initiative, which appeared to be all but irreversible, has been challenged by the Quad (United States, Japan, Australia and India).

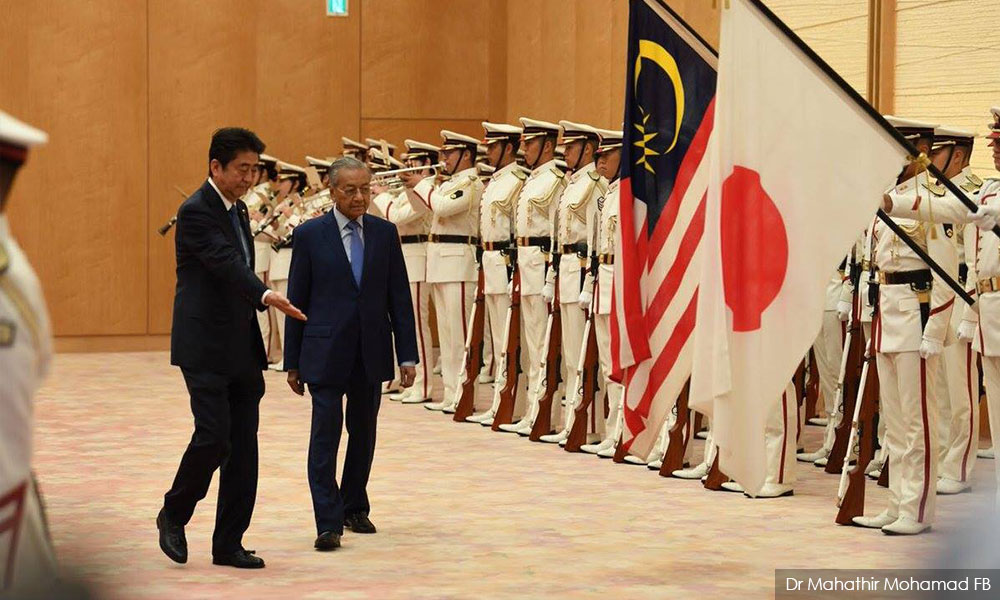

- Japan, one of the key powers in the Indo-Pacific region, continuing to shrink in terms of population, thus further heightening its insecurity.

These are dangerous times. There are some quaint parallels: the elan of the Vietnam War, when Communist forces pushed forward from the north to south in 1975; the fall of Kabul in 1989; the Russian incursion in Georgia in 2008; and the slow but organic militarisation of South China Sea from 2011 onwards when China, for the first time, referred to the area as its “core interest,” a term previously only reserved for Taiwan and Tibet.

But there is no telling if Harapan is aware of the whiplash effects of these world events. Political scientist Arthur Stein once warned of the importance of “relative gains” in international relations, wherein all great powers see gains and losses in zero-sum terms.

Granted, Malaysia has a foreign and defence policy that seems to be geared towards the centrality of ASEAN. But there is no telling if it wants to adjust to a post-US-Japanese world and the emerging Sino-Russian world order.

East Asia is entering this post-US-Japanese world. The US had always made it a point to keep Tokyo informed of any dramatic moves.

But now, at the speed of a tweet, Trump proceeded to announce the withdrawal of the US from the theater of the Middle East and South Asia, without notifying its staunchest East Asian allies Japan and South Korea.

Japan got its first taste of the ‘Nixon shock’ when the then-US president announced his plan to visit China in 1971, before Nixon announced his New Economic Programme, which included abandoning the gold standard.

The country would be shocked again when it received no thanks from Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah of Kuwait for its financial contribution to Operation Desert Storm led by then-president George Bush.

What Trump did in recent weeks must constitute a third shock for Japan – a major ally pulling out of two regions at the same time, even with the opposition of outgoing Secretary of Defense James Mattis.

By pulling out of Syria and Afghanistan, Japan must be reeling from the fear that its security relationship with Washington can be subject to the same forces that catapulted Trump to power – populism and the American far right.

China and Russia must also be smiling in glee, with the American admission of the impossibility of conducting simultaneous conflicts in two regions.

Malaysia is entering a world of uncertain geopolitical realities and flux.

What adds to the instability is the fact that it is ruled by a new coalition of four parties now beset by infighting – and one still due for a possibly messy transition at the top.

Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad still looks set to hands over the reins to Anwar Ibrahim, although there are signs that things are less than rosy behind the scenes – such as when the daughter of the latter quit her posts in government.

The new year seems likely to put Malaysia in a pinch as it looks ahead to 2020.

PHAR KIM BENG is a multiple award-winning head teaching fellow on China and the Cultural Revolution at Harvard University.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.