February 28, 2017

Is American Democracy Strong Enough for Trump?

The case against panic.

As an American citizen, I have been rather appalled, like many others, at the rise of Donald Trump. I find it hard to imagine a personality less suited by temperament and background to be the leader of the world’s foremost democracy.

“The End of History” (Liberal Demorcacy) under Threat

On the other hand, as a political scientist, I am looking ahead to his presidency with great interest, since it will be a fascinating test of how strong American institutions are. Americans believe deeply in the legitimacy of their constitutional system, in large measure because its checks and balances were designed to provide safeguards against tyranny and the excessive concentration of executive power. But that system in many ways has never been challenged by a leader who sets out to undermine its existing norms and rules. So we are embarked in a great natural experiment that will show whether the United States is a nation of laws or a nation of men.

President Trump differs from almost every single one of his 43 predecessors in a variety of important ways. His business career has shown a single-minded determination to maximize his own self-interest and to get around inconvenient rules whenever they stood in his way, for example by forcing contractors to sue him in order to be paid. He was elected on the basis of a classic populist campaign, mobilizing a passionate core of largely working-class voters who believe—often quite rightly—that the system has not been working for them. He has attacked the entire elite in Washington, including his own party, as being part of a corrupt cabal that he hopes to unseat. He has already violated countless informal norms concerning presidential decorum, including overt and egregious lying, and has sought to undermine the legitimacy of any number of established institutions, from the intelligence community (which he compared to Nazis) to the Federal Reserve (which he accused of trying to elect Hillary Clinton) to the American system of electoral administration (which he said was rigged, until he won).

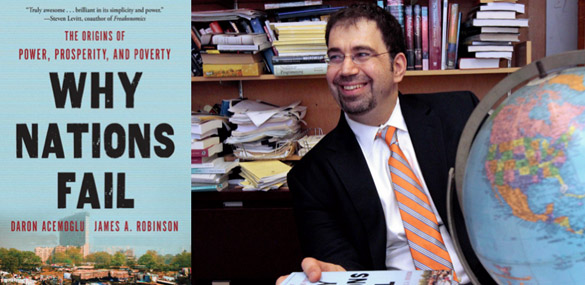

Dr. Daron Acemoglu–Nations can fail and why?

Daron Acemoglu, an economist who studies failing states, has argued that American checks and balances are not as strong as Americans typically believe: Congress is controlled by Trump’s party and will do his bidding; the judiciary can be shifted by new appointments to the Supreme Court and the federal judiciary; and the executive branch bureaucracy’s 4,000 political appointees will bend their agencies to the president’s will. The elites who opposed him are coming around to accepting him as normal president. He could also have argued that the mainstream media, which thinks of itself as a fourth branch holding the president accountable, is under relentless attack from Trump and his followers as politicized purveyors of “fake news.” Acemoglu argues that the main source of resistance now is civil society, that is, mobilization of millions of ordinary citizens to protest Trump’s policies and excesses, like the marches that took place in Washington and cities around the country the day after the inauguration.

Acemoglu is right that civil society is a critical check on presidential power, and that it is necessary for the progressive left to come out of its election funk and mobilize to support policies they favor. I suspect, however, that America’s institutional system is stronger than portrayed. I argue in my most recent book that the American political system in fact has too many checks and balances, and should be streamlined to permit more decisive government action. Although Trump’s arrival in the White House creates huge worries about potential abuses of power, I still believe that my earlier position is correct, and that the rise of an American strongman is actually a response to the earlier paralysis of the political system. More paralysis is not the answer, despite the widespread calls for “resistance” on the left.

Many institutional checks on power will continue to operate in a Trump presidency. While Republicans are celebrating their control of both houses of Congress and the presidency, there are huge ideological divisions within their coalition. Trump is a populist nationalist who seems to believe in strong government, not a small-government conservative, and this fracture will emerge as the new administration deals with issues from ending Obamacare to funding infrastructure projects. Trump can indeed change the judiciary, or more troubling, simply ignore court decisions and try to delegitimize those judges standing in his way. But shifting the balance in the courts is a very slow process whose effects will not be fully felt for a number of years. More overt attacks on the judiciary will produce great blowback, as happened when he attacked Federal District Judge Gonzalo Curiel during the campaign.

The Republican Trio—U.S. President-elect Donald Trump (centre), U.S. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and the Destruction of American Democracy

Trump will have enormous difficulties controlling the executive branch, as anyone who has worked in it would understand. Many of Trump’s Cabinet appointees, like James Mattis, Rex Tillerson and Nikki Haley, have already expressed views clearly at odds with his. Even if they are loyal, it takes a huge amount of skill and experience to master America’s enormous bureaucracy. It is true that the U.S. has a far higher number of political appointees than other democracies. But Trump does not come into office with a huge cadre of loyal supporters that he can insert into the bureaucracy. He has never run anything bigger than a large family business, and does not have 4,000 children or in-laws available to staff the U.S. government. Many of the new assistant and deputy secretaries will be Republican careerists with no particular personal ties to El Jefe.

Finally, there is American federalism. Washington does not control the agenda on a host of issues. Undermining Obamacare on a federal level will shift a huge burden onto the states, including those run by Republican governors who will have to balance budgets on the backs of the default from Washington. California, where I live, is virtually a different country from Trumpland and will make its own environmental rules regardless of what the President says or does.

Gen. James Mattis, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley–The Counter Trump Trio in the 45th Administration?

Gen. James Mattis, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley–The Counter Trump Trio in the 45th Administration?

In the end, Trump’s ability to break through institutional constraints will ultimately come down to politics, and in particular to the support he gets from other Republicans. His strategy right now is clear: He wants to use his “movement” to intimidate anyone who gets in the way of his policy agenda. And he hopes to intimidate the mainstream media by discrediting them and undermining their ability to hold him accountable. He is trying to do this, however, using a core base that is no more than a quarter to a third of the American electorate. There are already enough Republican senators who might break with the administration on issues like Russia or Obamacare to deny their party a majority in that body. And Trump has not done a great job since Election Day in alleviating the skepticism of anyone outside of his core group of supporters, as his steadily sagging poll numbers indicate. Demonizing the media on the second day of your administration does not bode well for your ability to use it as a megaphone to get the word out and persuade those not already on your side.

While I hope that all of these checks will operate to constrain Trump, I continue to believe that we need to change the rules to make government more effective by reducing certain checks that have paralyzed government. Democrats should not imitate the behavior of Republicans under President Barack Obama and oppose every single initiative or appointee coming out of the White House. It is absurd that any one of 100 senators can veto any mid-level executive branch appointee they want. In some respects, unified government will alleviate some of our recent dysfunctions, which Trump’s opponents need to recognize.

The last time Congress passed all of its spending bills under “regular order” was two decades ago. The U.S. desperately needs to spend more money on its military to meet challenges from countries like China and Russia; it has not been able to do so because the Defense Department was operating under the 2013 sequester that was in turn the product of congressional gridlock.

Or take infrastructure, which is the one part of the Trump agenda that I (and many Democrats) would support. The country has been gridlocked here as well, with the biggest source of opposition being the Tea Party wing of Trump’s own party, who would have stymied Hillary Clinton’s own initiative had she been elected instead. Trump has the opportunity now to break with the Freedom Caucus in the House and push for major new spending on infrastructure, which he could do with help from Nancy Pelosi’s Democrats.

Even so, such an initiative will face enormous obstacles due to the layers of regulation at federal and state levels. It is these small checks that make new infrastructure projects so costly and protracted. Anyone serious about the substance of this policy should see this an opportunity to streamline this process.

It is important to remember that one of the reasons for Trump’s rise is the accurate perception that the American political system was in many respects broken—captured by special interests and paralyzed by its inability to make or implement basic decisions. This, not a sudden affinity for Russia, is why the idea of a Putin-like strongman has suddenly gained appeal in America. The way democratic accountability is supposed to work is for the dominant party to be allowed to govern, and then be held accountable in two or four years time for the results it has produced.

Continued stalemate and paralysis will only convince people that the system is so fundamentally broken that it needs to be saved by a leader who can break all rules—if not Trump, then a successor

So I’m willing to let Trump govern without trying to obstruct every single initiative that comes from him. I don’t think his policies will work, and I believe the American people will see this very soon. However, the single most dangerous abuses of power are ones affecting the system’s future accountability.

What the new generation of populist-nationalists like Putin, Chávez in Venezuela, Erdogan in Turkey, and Orbán in Hungary have done is to tilt the playing field to make sure they can never be removed from power in the future. That process has already been underway for some time in America, through Republican gerrymandering of congressional districts and the use of voter ID laws to disenfranchise potential Democratic voters. The moment that the field is so tilted that accountability becomes impossible is when the system shifts from being a real liberal democracy to being an electoral authoritarian one.