January 12, 2018

Book Review: The Sustainable State: The Future of Government, Economy and Society

By: Cyril Pereira

Can planet Earth survive Asia’s economic drive?

The Sustainable State is Hong Kong-based environmentalist and author Chandran Nair’s second book, following Consumptionomics, published in 2011. Both call for urgent recognition of the looming ecological disaster for humanity. The book launch in Hong Kong’s trendy Lan Kwai Fong district on Nov. 13 was billed as a conversation between Nair, and Zoher Abdool Karim, the recently retired TIME Asia editor. Nair’s manifesto dominated. A bemused Zoher was the smiling prop. The audience could have gained more from meaningful interlocution.

Chandran Nair has been the town crier on environmental disaster for 20 years. He faults industrialization, capitalism, free enterprise and liberal economics, for destroying the ecosystems of rivers, forests, air and water on so vast a scale, that life itself is the price paid by the poorest across the developing world. Malnutrition, starvation, and lack of access to potable water, plagues many societies at subsistence level.

Resource curse

The developed world prospered from early industrialization to capture vast resources via conquest and colonization of Asia, Africa and Latin America, he writes. The poorest societies hold the richest deposits of minerals, fossil fuels and land for plantations of rubber, palm oil, tea and coffee. Pesticides and insecticides from Monsanto and others destroy their soils and ruin their water systems. They have also been too frequently run by kleptocrats.

What he calls the “externalities” of capitalist trade – environmental degradation, pollution, social dislocation, disease and malnutrition, impact the poorest disproportionately. Therein lies the supreme irony. Nair wants these externalities of economic activity priced and charged directly to corporations. He also wants individual accountability for wasteful consumption computed for carbon footprints and taxed to discourage waste.

Responsible development and consumer habits need to be enforced, if we are to survive our collective un-wisdom. How the corporations and individuals would agree to these principles, and the respective methods to calculate the amounts to pay, are undefined. Nair does not expect the culprits to volunteer. By the legal trick of defining corporations as ‘persons,’ companies can argue rights protecting individual citizens, under national Constitutions.

Migration to cities in Europe progressed over an extended period, without too much social disruption. Rural migration to cities in the developing economies is too rapid, within a compressed time-frame. Slum populations struggle without sanitation, proper housing, access to fresh water, electricity, or schooling for children, in too many cities across the developing world. This hollowing-out of rural populations is wasteful.

Rethink development

A whole new raft of public policies needs to evolve for ecological balance. Development plans to retain rural manpower and incentivize agricultural food security, are absent. Urban dwellers have to pay higher prices for natural produce, instead of buying packaged food in supermarkets. Efficient public transport systems have to be built to prevent city traffic gridlock. Electric vehicles have to replace fossil fuel engines.

Nair’s nightmare is the adoption by developing countries of the Western model for economic growth. India and China will constitute 30 percent of the global 10 billion by 2050. Add Africa, Latin America, and the rest of developing Asia to that, and the consequences of feckless industrialization, along with wasteful urban consumption, are too obvious. Nair advocates a radical overhaul of the development mindset.

Prescriptions from the developed world peddled by the World Bank and the IMF, in Nair’s mind, exceed Planet Earth’s healing capacity. Natural resource depletion and poisoning of the earth, water and air, must be stopped now. Hurricanes and typhoons destroying habitats and flooding societies, are increasing in frequency and ferocity. The consequences are all too real for climate change deniers.

Plastic Pollution in the World’s Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea

The weight of floating plastic in the oceans will soon exceed that of the global fish stock. This poison has entered our food chain, killing us slowly while choking sea life. Human overpopulation, food cultivation and de-forestation, wipes out wildlife at the rate of 30,000 species per year, according to Harvard biologist E. O Wilson. Now our collective irresponsibility will kill the oceans too.

Prioritize social equity

If replicating the Western growth model is madness, what are the alternatives? Nair moves into contentious territory on this. He calls for strong government and a revised development agenda. Rather than Hollywood-movie lifestyles, he suggests inclusive policies for all citizens to ensure clean water, electricity, sanitation, universal education and gainful employment as minimal benchmarks. Modest prosperity benefits all.

Social equity, well-being and protection of nature cannot be achieved without political legitimacy and effective rulership. Governance has been hijacked by Big Biz and sponsor politicians. Lobby groups target lawmakers. PR companies spin fakery for corporations and politicians. The mass media is co-opted through advertising and ownership. All at the expense of gullible citizens, led to believe they have some say every five years.

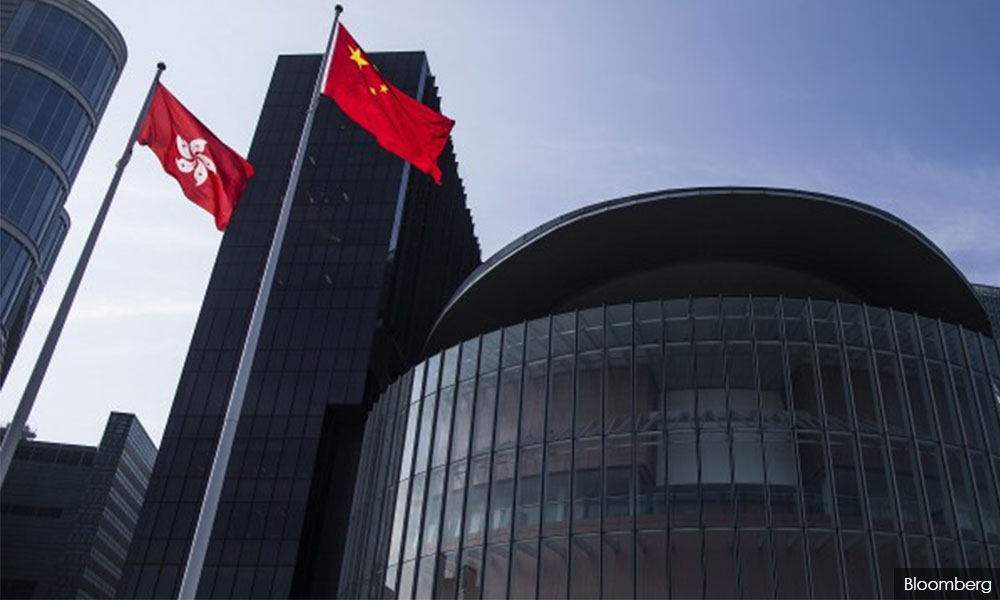

Strong state works

Nair contrasts the dysfunctions of India with the success of China. He skates on thin ice where individual rights and freedoms can be ignored, for the collective good. He says only a “strong” state has the mass mobilization capacity to marshal people, resources and investment, for sustainable development. To Nair, Hong Kong is a weak state unable to address basic public housing. He jests that a boss imposed by Beijing can fix that.

The European Union is a strong authority able to mandate socially responsible policy across its constituent members. Britain and the US are weak states floundering for effective governance, polarized by divisive populist politics. Nair is less interested in ideologies of the Left or Right, than in the State as effective authority for the common good. He wants the institutions of good governance strengthened at every level.

Oddly, Nair dismisses world governance as the solution. The United Nations, overly compromised by funding dependency and too timid to upset powerful voting blocs, is not his answer. Where then will the needed global course-correction come from? The issues Nair raises are urgent. Are we doomed to self-destruct by default anyway? If he has an answer, Nair has not articulated it in his books, or his public campaigns. Perhaps there might be a third book for that.