August 3, 2018

Speaking Truth to Power

by Ooi Kee Beng@Penang Institute

The easy access to information that the digital revolution has brought us has altered how we handle facts and how our cognitive processes work. Our reading habits today are characterised by impatience; we want information served fast, with insights offered as catchphrases that we can readily share. In Malaysia, the digital revolution of the last two decades has changed how information is controlled and disseminated. The firm government grip — since 1969 — has been loosened.

The technological shift has coincided with a rupture in the political order, starting with the falling out in 1998 between the country’s top two leaders, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad and his deputy Anwar Ibrahim. The event, which eventually led to the jailing of Anwar on charges of corruption and sodomy, sparked an anti-government protest movement called Reformasi. The bold activism of the movement almost caused the ruling coalition government to lose power in subsequent elections.

Reformasi caused Malaysian political consciousness to take a huge leap, but the promise of much-needed transition still hangs over the political scene today. The ability of Prime Minister Najib Razak and his government to hang on to power — to retain sufficient control over information, to aggravate racial and religious divides and to unleash the draconian power of its institutions when required — has diluted the optimism of the post-Mahathir age.

In part, the resilience of the political status quo depends greatly on the short memory of the Malaysian public for matters political. With threats, targeted arrests and dismissals, the government has been able to weaken the public imagining of it ever losing power. Its ability to tame the media has also been discouraging, the now defunct but highly popular Malaysian Insider website being a case in point.

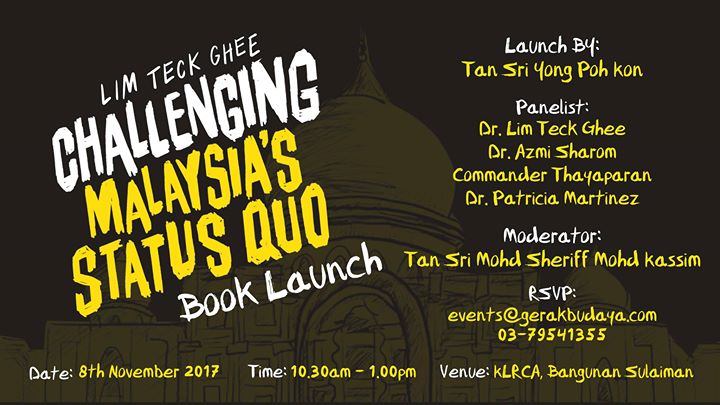

It is within this context that the recently published compilation of Lim Teck Ghee’s commentaries, straddling key political events of the last decade, should be evaluated. This volume is a good reminder of key events that took place in Malaysia since 2007. The issues involved have not changed much in character, which makes Lim’s opus a valuable undertaking, especially in the weeks leading up to the next general election on 9 May. Most of his writings were available at Heat Malaysia, but that website is now also defunct. The publication of this collection is a strong argument that books in print are still needed today.

Status Quo–UMNO-BN Government–dethroned in GE-14 (May 9, 2018)

Lim Teck Ghee received his first taste of realpolitik during the election of 1969 when he, then a PhD candidate in economics at the Australian National University, learned about keeping “the flame of dissent” alive from Dr. Tan Chee Khoon (“Mr Opposition”), who had just founded a new party, Gerakan, to challenge the ruling Alliance Party government, a political coalition led by the United Malays National Organisation. The young student helped prepare speeches and pamphlets for the fledgling party.

Lim’s association with Dr. Tan was a lesson in, as he puts it, “how an increasingly authoritarian and unaccountable … government would stop at nothing to maintain its hold on power — even to the extent of precipitating the May 1969 racial riots.”

On his return to Malaysia in 1971, Lim tried for the next two decades and more to combine his love of lecturing with his passion for social activism. His attempts to influence the system from within proved disappointing, however, and Lim left academia — and Malaysia — in 1994 to serve for a decade with the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific in Bangkok and the World Bank in Washington. In 2005 he returned to Malaysia.

The timing of his return was significant. Abdullah Badawi had succeeded Mahathir as Prime Minister, and his ability to deliver on his promise of reform was being tested. As one of Malaysia’s top economists, Lim wanted to make a contribution, so he set up the Centre for Public Policy Studies (CPPS). Together with former academic colleagues, he prepared five reports for submission to the government’s ninth Malaysia Plan.

One of these was “Corporate Equity Distribution: Past Trends and Future Policy”, which questioned the use of corporate equity figures as a measure of inter-ethnic wealth distribution. The report and its author came under immediate attack. Refutation of his claims and pressure from on high forced him to resign as director of the CPPS.

Lim went on to use a variety of platforms to publicise his research and his opinions on Malaysian politics and economics. A succinct writer, not known for pulling punches, he remains one of Malaysia’s more respected public intellectuals. Many of his recent writings have been about the decline in governance and ethics brought about by racial politics. Today, the line is never clear where affirmative action for the majority turns into suppression of minorities and begins a descent into apartheid of some form. A temporary cure insidiously becomes a permanent ill.

Packed into this volume are stimulating discussions written between 2006 and 2016, sorted under broad headings such as ethnic relations; race-based policies; religion; politics and economic models; education and history; and electoral reforms.

What I find of special interest are the chapters that make Lim distinctive among Malaysian commentators. These include the tongue-in-cheek “What’s It All About?”, “Guardians of the Status Quo” and “Corporate Equity”. In addition, there is a selection of interviews in which he pours his heart out on the state of his beloved country. Issues range from corruption to religious bigotry and the ruling party’s capture of the bureaucracy, to growing income inequality, falling standards of education and the culture of conflict-seeking politicking.

Malaysian politics has been undergoing deep changes in recent times. A growing Malay middle class that no longer sees identity politics as the only path and a Malay leadership that is not only split into several parties but also has on endless occasions been an international embarrassment for Malaysians in general, and for educated Malays in particular, have changed the nature of coalition building in a country that once took race-championing as the raison d’être for political participation.

Issues of governance have come to the fore and will undoubtedly play an important part in the election campaign. This trend has, sadly, whipped up an ugly response, and the ruling coalition in recent years has tried hard to turn its traditional brand of racial politics into divisive religious issues.

The quality of Malaysian politicians has also dropped markedly since Mahathir retired in 2004. They are now better known for making grandstanding statements, and the country’s public discourse has been riddled with issues that would be comical, if not for the racial and religious tensions they stoke.

To be sure, communal politics has always encouraged speeches to excite the target audience, but with the advent of the smart phone, all speeches are now available to the general public. Malaysia’s politicians appear to have a hard time adjusting to this. Trained to make ethnocentric claims to a closed audience, they find that their words are now megaphoned to stun a perplexed world, and in the process embolden the extremists among them to go public with their bigotry. This then informs the policy-making atmosphere.

Ludicrous debates such as whether a politician is a Malay first and a Malaysian second, whether the Arabic word “Allah” is legally reserved for Muslim use and whether the majority Malays will go the way of the “red Indians”, have been distracting nation building in Malaysia for decades, and continue to do so.

The Price of Defeat

A collection such as Lim Teck Ghee’s, filled with articles spanning more than a decade of entrenched political contestations, provides the reader with a much-needed guide on how to distinguish the signals from the noise when dealing with Malaysian politics.

![]()

The small elitists-Malay (Umnob) group know very well the significance of facts from fantasy , the difference between ” signal and noise”. They are just pretending and conveniently in self-denial, so that can perpetually feed their personal greed for power that can be abused for acquiring massive wealth for themselves and cronies , by suppressing the truth and information from the publc.

With the advent of IT, those days are gone.

Malaysians, East or West, especially the Malays, even from kampong are getting smarter by the hour.

This country needs leaders who are passionate and committed to serve the people with political will and policies of inclusiveness natural characteristics reflective of a Malaysian society , rather the artificially created Malay-race-religion based that will be a drag to the progress in terms of socio-economic, political development to the benefits of all , going forward.

In short, the elitIst-political leaders, regardless of race, religion or otherwise, from both sides of the divide, should wake up every morning, look into mirror, and remind themselves , each and every one ——STOP being a HYPOCRITE !

Worst still, on a national scale !

Pingback: Pressenza - Nonviolence Charter: progress report 13 (October 2018)

Pingback: Nonviolence Charter: progress report 13 (October 2018) | Ecumenics and Quakers