June 11, 2017

Critical Thinkers–Churchill and Orwell

A dual biography of Winston Churchill and George Orwell, who preserved democracy from the threats of authoritarianism, from the left and right alike.

Both George Orwell and Winston Churchill came close to death in the mid-1930’s—Orwell shot in the neck in a trench line in the Spanish Civil War, and Churchill struck by a car in New York City. If they’d died then, history would scarcely remember them. At the time, Churchill was a politician on the outs, his loyalty to his class and party suspect. Orwell was a mildly successful novelist, to put it generously. No one would have predicted that by the end of the 20th century they would be considered two of the most important people in British history for having the vision and courage to campaign tirelessly, in words and in deeds, against the totalitarian threat from both the left and the right. In a crucial moment, they responded first by seeking the facts of the matter, seeing through the lies and obfuscations, and then they acted on their beliefs. Together, to an extent not sufficiently appreciated, they kept the West’s compass set toward freedom as its due north.

It’s not easy to recall now how lonely a position both men once occupied. By the late 1930’s, democracy was discredited in many circles, and authoritarian rulers were everywhere in the ascent. There were some who decried the scourge of communism, but saw in Hitler and Mussolini “men we could do business with,” if not in fact saviors. And there were others who saw the Nazi and fascist threat as malign, but tended to view communism as the path to salvation. Churchill and Orwell, on the other hand, had the foresight to see clearly that the issue was human freedom—that whatever its coloration, a government that denied its people basic freedoms was a totalitarian menace and had to be resisted.

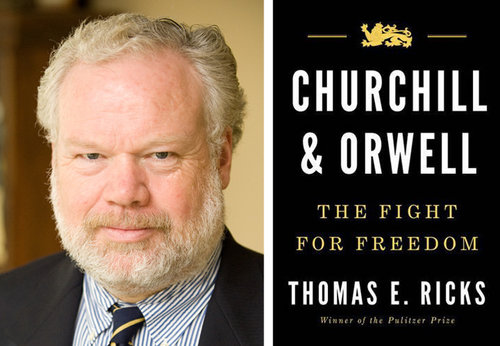

In the end, Churchill and Orwell proved their age’s necessary men. The glorious climax of Churchill and Orwell is the work they both did in the decade of the 1940’s to triumph over freedom’s enemies. And though Churchill played the larger role in the defeat of Hitler and the Axis, Orwell’s reckoning with the menace of authoritarian rule in Animal Farm and 1984 would define the stakes of the Cold War for its 50-year course, and continues to give inspiration to fighters for freedom to this day. Taken together, in Thomas E. Ricks’s masterful hands, their lives are a beautiful testament to the power of moral conviction, and to the courage it can take to stay true to it, through thick and thin.www.amazon.com

The Book, “Churchill And Orwell” is a Great Book. It is very well written and very interesting to read. The book is on the life and writing of both Orwell and Churchill and about how their thinking corresponds to a large degree. Since Churchill and Orwell never met, Thomas Ricks writes separate biographies and then works hard to deliver a common theme. He succeeds because these two men made cases for individual freedom better than anyone in their century.

Winston Churchill, a conservative, and George Orwell, a socialist, were two of the twentieth century’s great freedom fighters. Focusing on the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s, a period when democracy was losing ground to the deceptive idealism of communism and delusionalism of fascism, Ricks charts Churchill’s rise from the failure of Gallipoli and Orwell’s climb from obscurity, seeing both men as compelled to act, speak, and write in defense of human liberty and against all forms of authoritarianism. Both Churchill and Orwell believed in Individual Freedom for Humans. And they both knew that if Hitler conquered the world, that was the end of Individual Freedom for Human Kind.

During 1940, at a time when everyone agreed that Britain’s destruction was imminent, Churchill treated Neville Chamberlain and the appeasers (who were largely responsible) with respect, ordered no mass murders or arrests, and never assumed that, in this crisis and, of course, temporarily, Britain needed a touch of Nazi ruthlessness. Churchill read Hitler correctly from the beginning. He knew Hitler was out to conquer the world, and kill all the Jews and turn black and brown men into slaves to serve the Aryans who had blonde hair and blue eyes, and toes that pointed in a certain direction. Churchill knew that England would have to go to war with Hitler to prevent the Mad Man from conquering the world.

Orwell had always been the conservatives’ favorite Marxist, although he was a faithful socialist all his life. An obscure journalist until his breakthrough with “Animal Farm” (1945) and “Nineteen Eighty-Four” (1949), he hated totalitarianism in all forms but reserved special ire for the cant and fabrication that all governments employ and that his colleagues on the left accepted when it suited their beliefs. Everyone approves of Orwell’s classic statement that a lie in the service of a good cause is no less despicable than in the service of a bad cause. Yet it’s never caught on; our leaders routinely announce bad news as good news, and plenty of activists consider lying a useful tactic. Though Churchill had never met Orwell, but he admired him very much, and read his Nineteen Eighty-Four twice.

Winston Churchill and George Orwell were two of the most central figures of the twentieth century. Both Churchill and Orwell believed in Individual Freedom for Humans. They both knew that if Hitler conquered the world, that was the end of Individual freedom for human kind. And both came close to death in the 1930s: Orwell shot during the Spanish civil war, and Churchill struck by a car in New York City. Despite their prominence today, both were on the outskirts of power in the late 1930s as democracy was discredited and authoritarian rulers ascending. Yet both men re-defined the fight for freedom, and their posthumous influence on today’s struggles is clear. In Churchill and Orwell: The Fight For Freedom, Thomas Ricks examines these two men’s lives, their similarities and differences, and why their legacies will continue to matter.

The book comes at a prominent time. Today, we have a Hitler-like mad man in the White House, and the American Congress is dominated by a bunch of neo-Nazis.

From Thomas Ricks’ book, you’ll find the marriage of minds between a conservative (Winston Churchill) and a socialist (George Orwell). Both admiring each other very much. There’s a certain person in this blog who likes to write and repeat the same old right-left dichotomy from the right-wing perspective, like a broken record with absolutely no new idea, as if this dichotomy is a irreconcilable divergence. Yes, Americans today are more divided than ever by political ideology, as a recent Pew Research Center study makes clear. About a third of people on each side say of the other that its proponents “are so misguided that they threaten the nation’s well-being.” In my opinion, they’re both right about that. They both “are so misguided that they threaten the nation’s well-being.”

My prescription isn’t civility or dialogue, which though admirable are boring and in this case evidently impossible. Rather, my approach is “philosophical”: to try to confront both sides with the fact that their positions are incoherent. The left-right divide might be a division between social identities based on class or region or race or gender, but it is certainly not a clash between different political ideas. The arrangement of positions along the left-right axis – progressive to reactionary, or conservative to liberal, communist to fascist, socialist to capitalist, or Democrat to Republican – is conceptually confused, ideologically tendentious, and historically contingent. And any position anywhere along it is infested by contradictions.

These days, politicians are either ‘Right-wing,’ ‘Left-wing.’ or more occasionally, ‘Moderate.’ Donald Trump is right, Obama is left. The Tea Party is right wing, while the Green Party is left wing. Anarcho-syndicalists are leftists, while anarcho-capitalists are right-wingers. Everything and everyone is either left or right, liberal or conservative, Bolshevik or Bourgeois, and people fight long hard verbal wars over who belongs in which category. Yet, it seems to me that these are very poor classifications. At the outset, it beggars belief that all of humanity’s political movements can be charted on a simple uni-dimensional political spectrum. And, on closer examination, it appears that this is just the case you can’t reasonably classify every politician or political philosophy as either right-wing or left-wing.

For starters, how does one even define these terms? Just looking at what constitutes right vs left and you find that it varies from decade to decade and from country to country. Richard Nixon at his time was considered a conservative; but his policies by today’s measures would label him a liberal. In Europe, laissez faire markets are considered ‘liberal’ but in the US, they are ‘conservative.’ The term ‘right-wing’ in America refers to Republicans in general, but in Germany it’s reserved almost exclusively to Neo-Nazi groups. ‘Conservatives’, in the US talk a lot about the US Constitution, while ‘conservatives’ in Spain talk a lot about the monarchy. There’s no consistency. But it’s more than that though. When you really drill the matter down, you find that most issues just don’t fit on left right spectrum.

Take marriage for example. Recently in the US there has been a lot fuss over whether homosexual couples should be issued civil marriage licenses. Similar debates have been occurring in other countries as well. In general, those who oppose same-sex marriage are considered right-wing while those who favor it are considered left-wing. The former support traditional marriage norms while the later prefer a more inclusive approach. So far so good, but tell me: How does one classify a supporter of polygamous marriage licenses? On the one hand, it’s more inclusive to support it, so one would think that it’s a left wing position. On the other hand, the majority of support for it comes from otherwise right-wing, radical Mormon groups. Further, feminists who are classified as left-wing, generally oppose polygamy on the grounds that it’s usually at the expense of women. Yet you still can’t classify polygamy as right-wing because it’s certainly outside of the scope of ‘traditional marriage.’ Is this because polygamy is actually a ‘moderate’ position and between the right and left? Or perhaps, is it a radical position outside of the scope of left and right? The later, obviously. And you can apply this approach to other related issues. Bestiality? Group marriage? Abolishing civil marriage? Which of these are strictly right-wing and which are strictly left-wing policies? What about a person who supports same-sex unions, but opposes mixed-race unions? How about the reverse? There’s no consistent way to classify all possible positions on marriage on the left-right spectrum. The same with economics, military, social issues, and so forth.

So why are the terms ‘right’ and ‘left’ so widely used? Well, at one point it gives some sense. In the 18th and 19th centuries in Europe the Right were those who favored the established order, while the Left favored revolution and broad social change of one form or another. Most of Europe was governed by centuries old manarchies and aristocracies at the time and the established gentry were the Right. The Left were those political dissidents clamoring for changes such as representative government, civil liberties, free markets, socialism, nationalism etc. As such, French Republicans, Italian Unificationists, and Russian Bolsheviks could all be members of the Left, despite the fact that they had little, if anything, in common. At the same time, popes, kings, and magistrates could all be considered part of the Right despite the fact that few of them had much in common either.

As time wore on, however, left-wing movements survived long enough to become the new right-wing, and new ideologies formed which became the new left. Many new ideologies became throwbacks to older ideologies, and some ideologies fused both new and old ideas in novel ways. There were some movements which were both restorationist and revolutionary. It got to the point that the old rationale for the terms didn’t apply anymore but people would still apply them to the two largest factions, whatever those factions happened to be because it was easier than inventing new, more descriptive labels. As such ‘right’ and ‘left’ ceased to have any meaning except as labels for political factions.

These days, the terms right and left, and in American politics the term conservative and liberal, have mostly become labels with which to brand political opponents. These labels mean next to nothing concretely and are concerned solely with factionalism, which at the end of it all, is a waste of time if you want to understand matters and solve problems.