The following is Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s speech at the general debate of the 73rd session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York

Madam President,

1. I would like to join others in congratulating you on your election as the President of the Seventy-Third (73rd) Session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA).

2. I am confident with your wisdom and vast experience; this session will achieve the objectives of the theme for this session. I assure you of Malaysia’s fullest support and cooperation towards achieving these noble goals.

3. Allow me to also pay tribute to your predecessor, His Excellency Miroslav Lajcak, for his dedication and stewardship in successfully completing the work of the 72nd Session of the General Assembly.

4. I commend the Secretary-General and the United Nations staff for their tireless efforts in steering and managing UN activities globally.

5. In particular, I pay tribute to the late Kofi Annan, the seventh Secretary-General of the UN from 1997 – 2006, who sadly passed away in August this year. Malaysia had a positively strong and active engagement with the UN during his tenure.

Madam President,

6. The theme of this 73rd Session of General Assembly, “Making the United Nations Relevant to All People: Global Leadership and Shared Responsibilities for Peaceful, Equitable and Sustainable Societies” remains true to the aspiration of our founding fathers. The theme is most relevant and timely. It is especially pertinent in the context of the new Malaysia. The new Government of Malaysia, recently empowered with a strong mandate from its people, is committed to ensure that every Malaysian has an equitable share in the prosperity and wealth of the nation.

7. A new Malaysia emerged after the 14th General Election in May this year. Malaysians decided to change their government, which had been in power for 61 years, i.e., since independence. We did this because the immediate past Government indulged in the politics of hatred, of racial and religious bigotry, as well as widespread corruption. The process of change was achieved democratically, without violence or loss of lives.

8. Malaysians want a new Malaysia that upholds the principles of fairness, good governance, integrity and the rule of law. They want a Malaysia that is a friend to all and enemy of none. A Malaysia that remains neutral and non-aligned. A Malaysia that detests and abhors wars and violence. They also want a Malaysia that will speak its mind on what is right and wrong, without fear or favour. A new Malaysia that believes in co-operation based on mutual respect, for mutual gain. The new Malaysia that offers a partnership based on our philosophy of ‘prosper-thy-neighbour’. We believe in the goodness of cooperation, that a prosperous and stable neighbour would contribute to our own prosperity and stability.

9. The new Malaysia will firmly espouse the principles promoted by the UN in our international engagements. These include the principles of truth, human rights, the rule of law, justice, fairness, responsibility and accountability, as well as sustainability. It is within this context that the new government of Malaysia has pledged to ratify all remaining core UN instruments related to the protection of human rights. It will not be easy for us because Malaysia is multi-ethnic, multireligious, multicultural and multilingual. We will accord space and time for all to deliberate and to decide freely based on democracy.

Malaysia’s Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad speak during the General Debate of the 73rd session of the General Assembly at the United Nations in New York. NSTP/Video Grab UNWeb TV

Madam President,

10. When I last spoke here in 2003, I lamented how the world had lost its way. I bemoaned the fact that small countries continued to be at the mercy of the powerful. I argued the need for the developing world to push for reform, to enhance capacity building and diversify the economy. We need to maintain control of our destiny.

11. But today, 15 years later the world has not changed much. If at all the world is far worse than 15 years ago. Today the world is in a state of turmoil economically, socially and politically.

12. There is a trade war going on between the two most powerful economies. And the rest of the world feel the pain.

13. Socially new values undermine the stability of nations and their people. Freedom has led to the negation of the concept of marriage and families, of moral codes, of respect etc.

14. But the worse turmoil is in the political arena. We are seeing acts of terror everywhere. People are tying bombs to their bodies and blowing themselves up in crowded places. Trucks are driven into holiday crowds. Wars are fought and people beheaded with short knives. Acts of brutality are broadcast to the world live. Masses of people risk their lives to migrate only to be denied asylum, sleeping in the open and freezing to death. Thousands starve and tens of thousands die in epidemics of cholera.

15. No one, no country is safe. Security checks inconvenience travelers. No liquids on planes. The slightest suspicion leads to detention and unpleasant questioning.

16. To fight the “terrorists” all kinds of security measures, all kinds of gadgets and equipment are deployed. Big brother is watching. But the acts of terror continues.

17. Malaysia fought the bandits and terrorists at independence and defeated them. We did use the military. But alongside and more importantly we campaigned to win the hearts of minds of these people.

18. This present war against the terrorist will not end until the root causes are found and removed and hearts and minds are won.

19. What are the root causes? In 1948, Palestinian land was seized to form the state of Israel. The Palestinians were massacred and forced to leave their land. Their houses and farms were seized.

20. They tried to fight a conventional war with help from sympathetic neighbours. The friends of Israel ensured this attempt failed. More Palestinian land was seized. And Israeli settlements were built on more and more Palestinian land and the Palestinians are denied access to these settlements built on their land.

21. The Palestinians initially tried to fight with catapults and stones. They were shot with live bullets and arrested. Thousands are incarcerated.

22. Frustrated and angry, unable to fight a conventional war, the Palestinians resort to what we call terrorism.

23. The world does not care even when Israel breaks international laws, seizing ships carrying medicine, food and building materials in international waters. The Palestinians fired ineffective rockets which hurt no one. Massive retaliations were mounted by Israel, rocketing and bombing hospitals, schools and other buildings, killing innocent civilians including school children and hospital patients. And more.

24. The world rewards Israel, deliberately provoking Palestine by recognising Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

25. It is the anger and frustration of the Palestinians and their sympathisers that cause them to resort to what we call terrorism. But it is important to acknowledge that any act which terrify people also constitute terrorism. And states dropping bombs or launching rockets which maim and kill innocent people also terrify people. These are also acts of terrorism.

26. Malaysia hates terrorism. We will fight them. But we believe that the only way to fight terrorism is to remove the cause. Let the Palestinians return to reclaim their land. Let there be a state of Palestine. Let there be justice and the rule of law. Warring against them will not stop terrorism. Nor will out-terrorising them succeed.

27. We need to remind ourselves that the United Nations Organisation, like the League of Nations before, was conceived for the noble purpose of ending wars between nations.

28. Wars are about killing people. Modern wars are about mass killings and total destruction countrywide. Civilised nations claim they abhor killing for any reason. When a man kills, he commits the crime of murder. And the punishment for murder may be death.

29. But wars, we all know encourage and legitimise killing. Indeed the killings are regarded as noble, and the killers are hailed as heroes. They get medals stuck to their chest and statues erected in their honour, have their names mentioned in history books.

30. There is something wrong with our way of thinking, with our value system. Kill one man, it is murder, kill a million and you become a hero. And so we still believe that conflict between nations can be resolved with war.

31. And because we still do, we must prepare for war. The old adage says “to have peace, prepare for war”. And we are forever preparing for war, inventing more and more destructive weapons. We now have nuclear bombs, capable of destroying whole cities. But now we know that the radiation emanating from the explosion will affect even the country using the bomb. A nuclear war would destroy the world.

32. This fear has caused the countries of Europe and North America to maintain peace for over 70 years. But that is not for other countries. Wars in these other countries can help live test the new weapons being invented.

33. And so they sell them to warring countries. We see their arms in wars fought between smaller countries. These are not world wars but they are no less destructive. Hundreds of thousands of people have been killed, whole countries devastated and nations bankrupted because of these fantastic new weapons.

34. But these wars give handsome dividends to the arms manufacturers and traders. The arms business is now the biggest business in the world. They profit shamelessly from the deaths and destruction they cause. Indeed, so-called peace-loving countries often promote this shameful business.

35. Today’s weapons cost millions. Fighter jets cost about 100 million dollars. And maintaining them cost tens of millions. But the poor countries are persuaded to buy them even if they cannot afford. They are told their neighbours or their enemies have them. It is imperative that they too have them.

36. So, while their people starve and suffer from all kinds of deprivations, a huge percentage of their budget is allocated to the purchase of arms. That their buyers may never have to use them bothers the purveyors not at all.

Madam President,

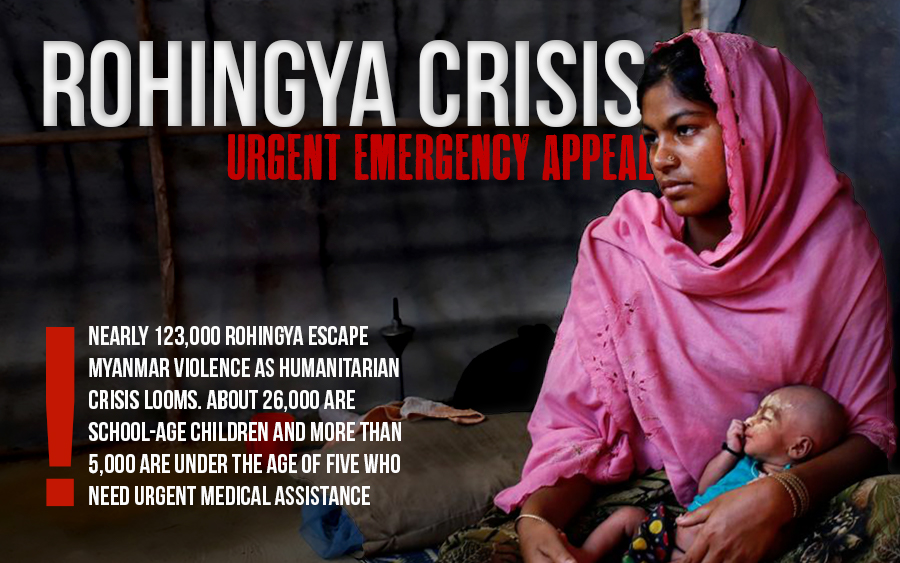

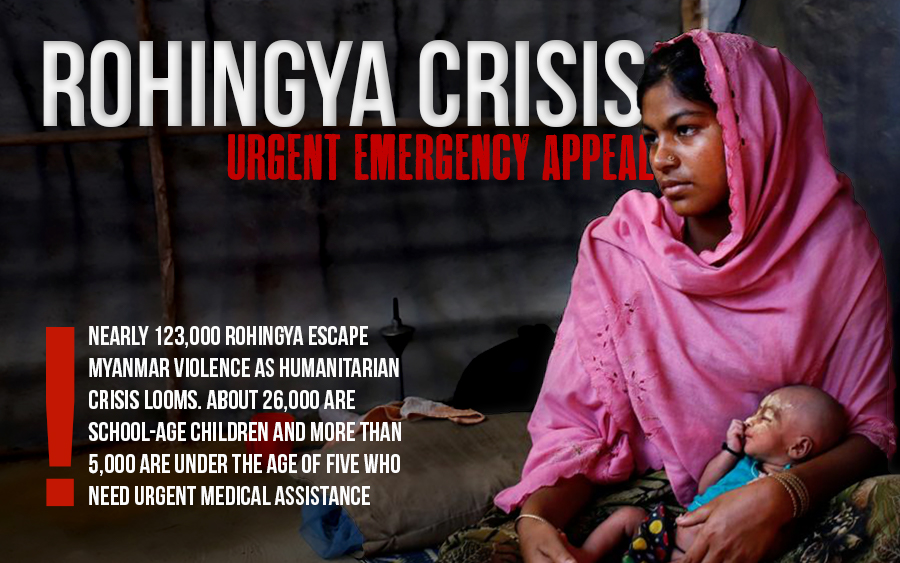

37. In Myanmar, Muslims in Rakhine state are being murdered, their homes torched and a million refugees had been forced to flee, to drown in the high seas, to live in makeshift huts, without water or food, without the most primitive sanitation. Yet the authorities of Myanmar including a Nobel Peace Laureate deny that this is happening. I believe in non-interference in the internal affairs of nations. But does the world watch massacres being carried out and do nothing? Nations are independent. But does this mean they have a right to massacre their own people, because they are independent?

Madam President,

38. On the other hand, in terms of trade, nations are no longer independent. Free trade means no protection by small countries of their infant industries. They must abandon tariff restrictions and open their countries to invasion by products of the rich and the powerful. Yet the simple products of the poor are subjected to clever barriers so that they cannot penetrate the market of the rich. Malaysian palm oil is labelled as dangerous to health and the estates are destroying the habitat of animals. Food products of the rich declare that they are palm oil free. Now palm diesel are condemned because they are decimating virgin jungles. These caring people forget that their boycott is depriving hundreds of thousands of people from jobs and a decent life.

39. We in Malaysia care for the environment. Some 48% of our country remains virgin jungle. Can our detractors claim the same for their own countries?

Madam President,

40. Malaysia is committed to sustainable development. We have taken steps, for example in improving production methods to ensure that our palm oil production is sustainable. By December 2019, the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO) standard will become mandatory. This will ensure that every drop of palm oil produced in Malaysia will be certified sustainable by 2020.

Madam President,

41. All around the world, we observe a dangerous trend to inward-looking nationalism, of governments pandering to populism, retreating from international collaborations and shutting their borders to free movements of people, goods and services even as they talk of a borderless world, of free trade. While globalisation has indeed brought us some benefits, the impacts have proven to be threatening to the independence of small nations. We cannot even talk or move around without having our voices and movement recorded and often used against us. Data on everyone is captured and traded by powerful nations and their corporations.

42. Malaysia lauds the UN in its endeavours to end poverty, protect our planet and try to ensure everyone enjoys peace and prosperity. But I would like to refer to the need for reform in the organisation. Five countries on the basis of their victories 70 over years ago cannot claim to have a right to hold the world to ransom forever. They cannot take the moral high ground, preaching democracy and regime change in the countries of the world when they deny democracy in this organisation.

43. I had suggested that the veto should not be by just one permanent member but by at least two powers backed by three non-permanent members of the Security Council. The General Assembly should then back the decision with a simple majority. I will not say more.

44. I must admit that the world without the UN would be disastrous. We need the UN, we need to sustain it with sufficient funds. No one should threaten it with financial deprivation.

Madam President,

45. After 15 years and at 93, I return to this podium with the heavy task of bringing the voice and hope of the new Malaysia to the world stage. The people of Malaysia, proud of their recent democratic achievement, have high hopes that around the world – we will see peace, progress and prosperity. In this we look toward the UN to hear our pleas.

I thank you, Madam President.