May 25, 2015

Why auditors can’t guarantee there was no fraud at 1MDB

by THE EDGE MALAYSIA

Published: 25 May 2015 7:00 AM@www.themalaysianinisder.com

The backers of 1Malaysia Development Bhd (1MDB) have argued that because international accounting firms like KPMG and Deloitte have signed off all 1MDB’s accounts from FY2010 to FY2014, this meant no money has gone missing and no fraud has occurred.

This argument has been used to justify the not-so-eloquent silence of the management and board of directors of 1MDB, who have refused to respond to questions posed to them about various transactions and the movements of billions of ringgit.

This argument has been used to justify the not-so-eloquent silence of the management and board of directors of 1MDB, who have refused to respond to questions posed to them about various transactions and the movements of billions of ringgit.

They hide behind that argument despite the fact that 1MDB has run into serious cash-flow problems and can no longer service its debts, and so many questions have been raised about the whereabouts and nature of the so-called Available-For-Sale Investments valued at RM13.38 billion in its accounts for financial year ended March 31, 2014.

Critics of 1MDB have been asked to back off and let the Auditor-General complete his work to review the audit of 1MDB.

The argument that because 1MDB’s accounts have been signed off by auditors meant that no fraud has occurred and that money was not missing is flawed. It shows that these people do not know what they are talking about.

They have badly misinterpreted, deliberately or otherwise, the role of external auditors and they do not understand the meaning of an auditor’s report when the auditors sign off the financial statement of a company.

There are no auditors in this world who will agree that their signing off on an account can in any way or form be interpreted to mean that they confirm or guarantee that the accounts are completely true, accurate and do not contain any misstatements, by fraud or error.

The International Standards for Auditing guidelines for auditors state that the external auditor is responsible for obtaining reasonable assurance that the financial statements, taken as a whole, are free from material misstatement, whether caused by fraud or error.

That reasonable assurance is based on the external auditor trusting that the management and board of a company have carried out their fiduciary duties and were not involved in any fraud or have concealed any fraud.

Owing to the inherent limitations of an audit, there is an unavoidable risk that material misstatement may not be detected, even when the audit is planned and performed in accordance with international accounting standards.

The risk of fraud is higher than those of error because fraud usually involves sophisticated and carefully organised schemes designed to conceal it.

Therefore, it is not the role of an external auditor to determine whether fraud has actually occurred. That is the responsibility of the country’s criminal and legal system.

Indeed, auditors call the discrepancy between what the public expects and what auditors do as an “expectations gap”.

Indeed, auditors call the discrepancy between what the public expects and what auditors do as an “expectations gap”.

Let us now take a closer look at Deloitte’s audit report issued to 1MDB on November 5, 2014, for the financial year ended March 31, 2014. The fact that it was issued more than seven months after the year-end in itself should raise concerns.

Para 2: The directors of the company are responsible for the preparation of these financial statements so as to give a true and fair view. The directors are also responsible for such internal control as the directors determine what is necessary to enable the preparation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error.

Para 3: Our (Deloitte) responsibility is to EXPRESS AN OPINION on these financial statements based on our audit… and perform the audit to obtain REASONABLE assurance about whether the financial statements are free from material misstatement.

The above remarks by Deloitte is a standard template statement issued by auditors to most companies. What is important to note are the following:

1. The directors of 1MDB are ultimately responsible for the accounts in so far as they give a true and fair view. The directors are also responsible for internal controls that are necessary to enable the financial statements to be free from misstatements, whether due to fraud or error. This is NOT the responsibility of the auditor.

2. The auditors only express an opinion that they, as external auditors, have done what is necessary to obtain REASONABLE assurance about whether the financial statements are free from material misstatement.

3. Critically, the external auditors DO NOT express an opinion on the effectiveness of the company’s internal controls.

In short, while auditors should be able to detect defective keeping of accounting records, they cannot detect falsified accounting documents. And neither can they question management decisions on, say, an investment that it made.

The questions asked of 1MDB mainly relate to the effectiveness of internal controls and corporate governance:

– Who approved the agreements and the various payments made since 2009?

– Why were funds diverted from what they were approved for? Why was money sent to an account controlled by Jho Low?

– Why did 1MDB overpay for the power assets, the Penang land and the commissions to the bankers like Goldman Sachs?

– Who verified and agreed to pay the US$700 million to PetroSaudi, purportedly as settlement of a loan?

– Why was Jho Low giving instructions to the management on matters of 1MDB?

– Who agreed to the Aabar options and then agreed to a termination settlement that cost 1MDB US$1 billion?

All these major issues that have been raised are about internal controls, decision-making and corporate governance at 1MDB.

Deloitte, in their audit report, had clearly stated they are NOT expressing any opinion on the effectiveness of 1MDB’s internal controls.

So, please stop passing the buck to Deloitte or using the fact that it signed off on the accounts, to say that nothing wrong has happened and that everything at 1MDB is fine.

And since the auditor-general has merely been asked to audit the work of Deloitte, it is most likely the case that his mandate is no more than that of Deloitte.

It is clear. The board of directors is responsible in ensuring the accounts are true and fair. The board is responsible for internal controls to ensure there is no fraud.

The auditor only expresses a reasonable opinion. Nothing more.

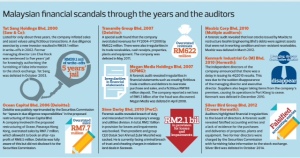

The corporate sector, at home and around the world, is littered with many examples of corporate fraud that escaped the scrutiny of auditors. In a few cases, auditors were also culpable, if not outright complicit.

The largest corporate fraud ever in the world was US energy giant Enron, whose US$78 billion market value was wiped out in days. Former Enron President Jeff Skilling is still serving a 24-year jail term.

And its auditors, Arthur Andersen, one of the Big Four accounting firms in the world then, had to cease operations.

Bernard Madoff’s US$65 billion Ponzi scheme is evidence that funds under management, with third-party valuations by international institutions, may also be subject to misappropriations and fraud. Madoff is currently serving a 150-year sentence in prison.

An article was published in the November 20, 2012 issue of Forbes magazine, on how Hewlett-Packard (HP) lost US$5 billion on a US$11.1 billion acquisition.

HP said it had to write down the value of UK software company Autonomy because it was inflated through serious accounting improprieties, misrepresentation and disclosure failures.

That scam tainted all the auditors involved – Deloitte as the auditors for Autonomy and Ernst & Young, the auditors for HP – for not detecting the fraud.

Need we say more? – May 25, 2015.

The fact is, (cash)money is missing in the 1 MDB account at its account with a Singapore bank.

”The International Standards for Auditing guidelines for auditors state that the external auditor is responsible for obtaining reasonable assurance that the financial statements, taken as a whole, are free from material misstatement, whether caused by fraud or error.”

But should not the International Standards for Auditing guidelines for auditors to also state the external auditor be responsible for ”reasonable assurance ” that had turned ”unreasonable ” of the financial statements, that could end up in the Auditors Disciplinary Board or court due the misjudgment , withholding unsubstantiated information or condoning material misstatement of errors of their own or 1 MDB’s board and its accounts ?

The statutory audit mandated by law is generally compliance audit which complies with the laws and accounting/auditing standards but may not indicate any cases of mismanagement-fraud-corruption. There may may some suspicions and these may have been brought to the attention of the AC and Directors the suspicions cannot be included in the Audit Certificate. Further the cases may be on the margins of these risks for which the Directors may have provided explanations which may be acceptable to the Statutory Auditors. In some cases as in the case of Satyam India the External Auditor went along with the Directors and gave unqualified Certificate perceived to be due to ensure future business.

The Internal Auditors are the best persons but then they are only required to report to AC who may chose to raise the matter with the Board. The report of the AC as included in the Annual Reports of Bursa listed and other companies is generally a reproduction of the Bursa requirements and statement that they have had discussions with the IAD and External Auditors but nothing else is revealed. Further when shareholders inquire about any findings of the IAD/AC the standard reply is that the AC has acted in the best interest of the shareholders and that they are men of integrity/ethics and that shareholders are expected to have total trust in them.

It is perceived that Transparency and Accountability are merely slogans as they cannot be verified.

It may be noted that ESOS was intended to be to reward human resources in times of sterling financial reports. But ESOS has been extended to Directors including AC members. The best form of reward to Directors and Human Resources would be higher fees to Directors and Bonuses/promotions to Human Resources but this mode would make these rewards subject to Income Tax and thus may find less favor whereas ESOS provides CAPITAL GAINS WHICH ARE TAX EXEMPT as the ESOS exercise price is generally at a discount which can be anything from 10% to more than 50%. Some Directors may get ESOS ranging from few hundred thousands to some millions of shares for Directors whereas from thousands to higher number of shares. These ESOS are generally only exercised where the share prices have gone up whereas where the share price is below the ESOS exercising price the entitlement are rarely exercised as in one case where none of th granted ESOS have been exercised from the past five years as the exercise rate was just below RM3.00 which was fixed when the share price was much higher but then the price started sliding and to-day the price is about RM1.17 per share.

[Refer to Announcements to Bursa and in some cases the Annual Report where the exercised price may be disclosed.]

I still can remember the Post Master who did not bank in the takings on Friday and used the money in scheme to double it and bank in the amount collected on Friday on Monday. The scheme failed as the Ponzi Man ran away with the “spoon”. The rest is all about sentence and the appearance of the “period” which usually signals the end of a sentence.

Like many others, this case has been over-politicized. But the publicity serves the people well – at least it made it known that the government is being watched.

At the end of the day, audits are not what the figures show you… rather they are what you get after you have “massaged” them.. It is legal criminality.

“Why auditors can’t guarantee there was no fraud at 1MDB”

Isa Manteqi,

You have a good point there.

“…Deloitte is 1MDB’s third auditor since it was set up in 2009 to spearhead development in strategic sectors. 1MDB’s main business is property development and utilities, such as power and water plants.

It has taken a severe beating to its image and reputation after it had signed off 1MDB’s 2014 accounts in early November last year but several weeks later, the fund struggled to repay a RM2 billion loan.

“Deloitte Malaysia has become the laughing stock of the accounting and financial community with their highly questionable audit of 1MDB and it being made the shield by the Malaysian government to defend the company.

“In particular, how is it possible that Deloitte’s audit partner, Ng Yee Hong, had gotten it so wrong by signing off its March 2014 accounts on November 5, 2014 without any qualifications when 1MDB was in all practical terms, insolvent.”

Deloitte, the DAP national publicity secretary said, had signed off the accounts by saying that its “funding facilities and net cash flow” from its operations were sufficient to cover its cash-flow needs.

“However, by the end of the same month of November, 1MDB was forced to repeatedly extend its repayment of a RM2 billion loan which was due…”

http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/deloitte-must-leave-no-stone-unturned-in-latest-1mdb-audit-says-tony-pua#sthash.AbNUEjTC.dpuf

October 23, 2008 – http://anak-reformasi.blogspot.com/2008_10_23_archive.html

http://www2.hmetro.com.my/articles/Inginberbaktisepertibapa/Umno/article_html

3 April 2009 – http://www.mstar.com.my/berita/berita-semasa/2009/04/03/anakanak-yakin-najib-mampu-berkhidmat-cemerlang/

PM’s son a partner in Deloitte, 1MDB’s auditors

Story by Chan Quan Min

quanmin@kinibiz.com

Nizar Najib a budding politician and chartered accountant with more than 10 years in consulting and auditing experience is a partner of 1Malaysia Development Bhd’s auditors, Deloitte.

http://www.kinibiz.com/story/corporate/83331/pm%E2%80%99s-son-a-partner-in-deloitte-1mdb%E2%80%99s-auditors.html

“…Speakers’ profiles

Nizar Najib is the Energy & Resources (E&R) Leader for Malaysia and also the

Corporate Finance Executive Director within the Financial Advisory Services

practice. He has more than 12 years of consulting and auditing experience

for government, multinational companies, local public listed and large private

enterprises. His wide range of experience includes assignments in the areas

of corporate strategy CFO services, mergers and acquisitions, performance

improvement, systems testing, financial modeling, and management and

technical due diligence.

Nizar holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Nottingham,

United Kingdom. He is a member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants

England and Wales and also a member of the Malaysian Institute of

Accountants…”

Click to access my-er-oil-gas-summit-2015-noexp.pdf

http://www.businesstoday.net.my/the-growth-realities-for-og-industry/

Aug 08, 2012 – http://www.accountingweb.co.uk/article/deloitte-caught-standard-chartered-scandal/530321

April 6, 2014 – http://business.financialpost.com/legal-post/livent-auditor-deloitte-ordered-to-pay-84-8-million-for-failing-detect-fraud

Jan 4 2015 – http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/Corporate-News/Deloitte-on-the-spot-over-role-Mumias-Sugar-accounting-scandal/-/539550/2578514/-/2e0ldv/-/index.html

Oct 21, 2014 – http://www.michaelmeacher.info/weblog/2014/10/the-big-4-accountancy-firms-corrupt-fiddles-for-the-banks-must-be-stopped/

Some 13 years after Enron, auditors still can’t stop managers cooking the books. Time for some serious reforms…

“Do people panic when the IRS descends on them, or when your friendly neighbourhood auditor that you pay does?” asks Prem Sikka of the University of Essex. “Companies should be directly audited by an arm of the regulator.” Small-government types hate either prospect.

The most elegant solution comes from Joshua Ronen, a professor at New York University.

He suggests “financial statements insurance”, in which firms would buy coverage to protect shareholders against losses from accounting errors, and insurers would then hire auditors to assess the odds of a mis-statement.

The proposal neatly aligns the incentives of auditors and shareholders—an insurer would probably offer generous bonuses for discovering fraud.

Unfortunately, no insurer has offered such coverage voluntarily. New regulation may be needed to encourage it.

Finally, the answer for free-market purists is to scrap the legal requirement for audits.

Today accountants enjoy a captive market, and maximise profits by doing the job as cheaply as possible.

If clients were no longer forced to buy audits, those rents would disappear.

In order to stay in business, the Big Four would then have to devise a new type of audit that investors actually found useful.

This approach would probably yield detailed reports designed with shareholders’ interests in mind.

But it would also allow hucksters to peddle unaudited penny stocks to gullible investors.

Whether government should protect people from bad decisions is a question with implications far beyond accounting.”

Dec 13th 2014 – Accounting scandals – The dozy watchdogs – http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21635978-some-13-years-after-enron-auditors-still-cant-stop-managers-cooking-books-time-some

You be the judge.

“Why auditors can’t guarantee there was no fraud at 1MDB”

Accounting scandals – The dozy watchdogs

Some 13 years after Enron, auditors still can’t stop managers cooking the books. Time for some serious reforms

Dec 13th 2014 | NEW YORK | From the print edition

NO ENDORSEMENT carries more weight than an investment by Warren Buffett. He became the world’s second-richest man by buying safe, reliable businesses and holding them for ever. So when his company increased its stake in Tesco to 5% in 2012, it sent a strong message that the giant British grocer would rebound from its disastrous attempt to compete in America.

But it turned out that even the Oracle of Omaha can fall victim to dodgy accounting. On September 22nd Tesco announced that its profit guidance for the first half of 2014 was £250m ($408m) too high, because it had overstated the rebate income it would receive from suppliers. Britain’s Serious Fraud Office has begun a criminal investigation into the errors. The company’s fortunes have worsened since then: on December 9th it cut its profit forecast by 30%, partly because its new boss said it would stop “artificially” improving results by reducing service near the end of a quarter. Mr Buffett, whose firm has lost $750m on Tesco, now calls the trade a “huge mistake”.

No sooner did the news break than the spotlight fell on PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), one of the “Big Four” global accounting networks (the others are Deloitte, Ernst & Young (EY) and KPMG). Tesco had paid the firm £10.4m to sign off on its 2013 financial statements. PwC mentioned the suspect rebates as an area of heightened scrutiny, but still gave a clean audit.

PwC’s failure to detect the problem is hardly an isolated case. If accounting scandals no longer dominate headlines as they did when Enron and WorldCom imploded in 2001-02, that is not because they have vanished but because they have become routine. On December 4th a Spanish court reported that Bankia had mis-stated its finances when it went public in 2011, ten months before it was nationalised. In 2012 Hewlett-Packard wrote off 80% of its $10.3 billion purchase of Autonomy, a software company, after accusing the firm of counting forecast subscriptions as current sales (Autonomy pleads innocence). The previous year Olympus, a Japanese optical-device maker, revealed it had hidden billions of dollars in losses. In each case, Big Four auditors had given their blessing.

And although accountants have largely avoided blame for the financial crisis of 2008, at the very least they failed to raise the alarm. America’s Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation is suing PwC for $1 billion for not detecting fraud at Colonial Bank, which failed in 2009. (PwC denies wrongdoing and says the bank deceived the firm.) This June two KPMG auditors received suspensions for failing to scrutinise loan-loss reserves at TierOne, another failed bank. Just eight months before Lehman Brothers’ demise, EY’s audit kept mum about the repurchase transactions that disguised the bank’s leverage.

The situation is graver still in emerging markets. In 2009 Satyam, an Indian technology company, admitted it had faked over $1 billion of cash on its books. North American exchanges have de-listed more than 100 Chinese firms in recent years because of accounting problems. In 2010 Jon Carnes, a short seller, sent a cameraman to a biodiesel factory that China Integrated Energy (a KPMG client) said was producing at full blast, and found it had been dormant for months. The next year Muddy Waters, a research firm, discovered that much of the timber Sino-Forest (audited by EY) claimed to own did not exist. Both companies lost over 95% of their value.

Of course, no police force can hope to prevent every crime. But such frequent scandals call into question whether this is the best the Big Four can do—and if so, whether their efforts are worth the $50 billion a year they collect in audit fees. In popular imagination, auditors are there to sniff out fraud. But because the profession was historically allowed to self-regulate despite enjoying a government-guaranteed franchise, it has set the bar so low—formally, auditors merely opine on whether financial statements meet accounting standards—that it is all but impossible for them to fail at their jobs, as they define them. In recent years this yawning “expectations gap” has led to a pattern in which investors disregard auditors and make little effort to learn about their work, value securities as if audited financial statements were the gospel truth, and then erupt in righteous fury when the inevitable downward revisions cost them their shirts.

The stakes are high. If investors stop trusting financial statements, they will charge a higher cost of capital to honest and deceitful companies alike, reducing funds available for investment and slowing growth. Only substantial reform of the auditors’ perverse business model can end this cycle of disappointment.

Born with the railways

Auditors perform a central role in modern capitalism. Ever since the invention of the joint-stock corporation, shareholders have been plagued by the mismatch between the interests of a firm’s owners and those of its managers. Because a company’s executives know far more about its operations than its investors do, they have every incentive to line their pockets and hide its true condition. In turn, the markets will withhold capital from firms whose managers they distrust. Auditors arose to resolve this “information asymmetry”.

Early joint-stock firms like the Dutch East India Company designated a handful of investors to make sure the books added up, though these primitive auditors generally lacked the time or expertise to provide an effective check on management. By the mid-1800s, British lenders to capital-hungry American railway companies deployed chartered accountants—the first modern auditors—to investigate every aspect of the railroads’ businesses. These Anglophone roots have proved durable: 150 years later, the Big Four global networks are still essentially controlled by their branches in the United States and Britain. Their current bosses are all American.

As the number of investors in companies grew, so did the inefficiency of each of them sending separate sleuths to keep management in line. Moreover, companies hoping to cut financing costs realised they could extract better terms by getting an auditor to vouch for them. Those accountants in turn had an incentive to evaluate their clients fairly, in order to command the trust of the markets. By the 1920s, 80% of companies on the New York Stock Exchange voluntarily hired an auditor.

Unfortunately, Jazz Age investors did not distinguish between audited companies and their less scrupulous peers. Among the miscreants was Swedish Match, a European firm whose skill at securing state-sanctioned monopolies was surpassed only by the aggression of its accounting. After its boss, Ivar Kreuger, died in 1932 the company collapsed, costing American investors the equivalent of $4.33 billion in current dollars. Soon after this the Democratic Congress, cleaning up the markets after the Great Depression, instituted a rule that all publicly held firms had to issue audited financial statements. Britain had already brought in a similar policy.

Just what that audit should entail, however, remained an open question. Some legislators proposed that the newly formed Securities and Exchange Commission should conduct audits itself. However, Congress decided to let accountants determine for themselves what their reports would contain. That ill-fated choice paved the way for a watering-down of the audit report that plagues markets to this day.

Even in the age of voluntary audits, accountants were rarely held accountable for their clients’ sins. As a British judge declared in 1896, “An auditor is not bound to be a detective…he is a watchdog, not a bloodhound.” The advent of mandatory audits exacerbated this hazard, because auditors no longer needed to provide value to investors in order to induce companies to buy their services. Without any external rules on what the profession had to verify, it quickly began reducing its own responsibility. Having once offered a “guarantee” that statements were correct, auditors soon moved on to mere “opinions”.

The modern audit does not even provide an opinion on accuracy. Instead, the boilerplate one-page pass/fail report in America merely provides “reasonable assurance” that a company’s statements “present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of [the company] in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)”. GAAP is a 7,700-page behemoth, packed with arbitrary cut-offs and wide estimate ranges, and riddled with loopholes so big that some accountants argue even Enron complied with them. (International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), which are used outside the United States, rely more on broad principles). “An auditor’s opinion really says, ‘This financial information is more or less OK, in general, so far as we can tell, most of the time’,” says Jim Peterson, a former lawyer for Arthur Andersen, the now-defunct accounting firm that audited Enron. “Nobody has paid any attention or put real value on it for about 30 years.”

Although auditors cannot hope to verify more than a tiny fraction of the millions of transactions their clients conduct, in order to comply with the standards they physically count inventories, match invoices with shipments and bank statements, and consult experts on the plausibility of management’s estimates. Most firms’ records are at least tweaked during the process. And even though private businesses do not have to undergo audits, most mid-size firms buy one anyway, because banks rarely lend to unaudited borrowers. The recent spate of frauds in China, where auditing practices are far laxer, shows that markets are right to assign a premium to companies that receive a Western accountant’s approval.

Those conflicts of interest

Even so, the misaligned incentives built into auditing all but guarantee that accountants will fall short of investors’ needs. The beneficiaries of the service—current and prospective shareholders—pay for it indirectly or not at all, while the purchasers buy it only because they are required to. As a result, companies tend to select auditors who will provide a clean opinion as cheaply and quickly as possible. Similarly, accountants who discover irregularities may be better off asking management to make minor adjustments, rather than blowing the whistle on a mis-statement that could embroil their firm in costly litigation.

The audit industry cites four main factors that counteract this conflict of interest. One is the separation of the audit committee from management. Ever since the Sarbanes-Oxley corporate-governance reform of 2002, American auditors have been chosen not by CEOs or CFOs but by a subcommittee of the board of directors. In theory, this should ensure they are selected and compensated with shareholders’ interests in mind. In practice, audit committees are easily captured by management. One academic study found that companies with a senior executive previously employed by a member of the Big Four are far more likely to be audited by that firm than its competitors. The head of Tesco’s audit committee once worked at PwC.

Another potential defence against conflict is reputation: an auditor known for shoddy work will lose business, because investors will not believe its reports. That may have been true long ago, when companies could choose among many accountants. But today only the Big Four have the scale to audit giant multinationals; together, they audit firms that make up 98% of the value of American stockmarkets. And since all of them have approved statements later revealed to be incorrect, none enjoys a reputation much above the others. Companies do not drop Big Four auditors just because the firm failed to catch an error at a different client.

A potentially stronger deterrent is legal risk. Ever since a 1969 Supreme Court case found auditors liable for failing to detect fraud, accountants have feared litigation from shareholders. Those concerns were vindicated when Arthur Andersen, a peer of the Big Four, was brought down by lawsuits related to the Enron scandal. But it took the biggest accounting failure in history to overcome the legal protections auditors enjoy. Short of an Enron-scale disaster, the Big Four have generally beaten back suits or settled them for affordable sums. In America, plaintiffs have to demonstrate intentional recklessness by the accountants in order to reach trial. And in 2005, the Supreme Court ruled that shareholders must prove a direct causal link between a defendant’s activity and a declining stock price in order to claim damages. Despite the auditors’ abysmal performance before the financial crisis, legal claims against them have been modest: this April an arbitration council ruled that EY was not at fault in Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy.

That leaves only one truly effective force: regulation. In 1933, during a hearing on a law that helped establish mandatory audits, an industry spokesman told Congress that auditors were fully independent from the accounting staffs of their clients. “You audit the controllers?” a sceptical senator inquired. “Who audits you?” “Our conscience,” came the meek reply.

If there was any doubt that this was an insufficient safeguard, the Enron scandal eliminated it. In response, the Sarbanes-Oxley act limited the consulting work American accounting firms could do for audit clients, and set up the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), a non-profit intended to play Big Brother to the Big Four. James Doty, its chairman, says that “We see [auditors] as professional people subject to pressures to compromise their independence.” In 2004 Britain established a similar watchdog, which is part of the Financial Reporting Council.

These bodies have audited the auditors with gusto. They check the most delicate sections of risky audits; prepare reports on each accounting firm; and levy multimillion-dollar fines when displeased. Last month the PCAOB announced that of the 219 audits of financial statements for 2013 it had reviewed, 85 required more work and should not have been approved. Since the board’s creation, restatements have declined significantly. The PCAOB “is what’s on the mind of the everyday auditor today”, says Joe Ucuzoglu of Deloitte. “Their work is going to have to stand up to inspection scrutiny. High-quality work is rewarded, but lapses can have severe consequences for their compensation.”

Improving the bite

The PCAOB is rightly proud of the improvements in audit quality on its watch. But the regulators themselves admit that though government inspections may help reduce gross negligence, they cannot convert auditors into the trusty allies against rogue management that shareholders need. For that, only structural reform will do.

The easiest improvement would be an expansion of the audit report. Britain has already replaced the single-page pass/fail statement with a more detailed summary of auditors’ activities and areas of focus. Bob Moritz, the chairman of PwC’s American arm, says that reports would be more useful if accountants audited a wider range of “value drivers”, such as drug pipelines for pharmaceutical companies or oil reserves for energy companies.

Another help would be greater competition. Because the Big Four specialise in different industries in each country, many companies have only two or three candidates to audit them. High concentration has also hamstrung the courts: in 2005 America’s Justice Department agreed not to prosecute KPMG for marketing illegal tax shelters, largely because the government feared that a conviction would destroy the firm and further reduce the numbers in the oligopoly. But antitrust action against the Big Four would make matters worse: breaking one up would leave even fewer firms with the necessary scale. Ironically, the way to increase competition would be for a group of weaker networks to consolidate into a new global player. However, even KPMG, the smallest of the Big Four, is larger than the next four firms combined.

Proposals to modify how auditors are chosen or paid invariably involve trade-offs. The simplest would be to shield the audit committee even more from management influence, by having it nominated by a separate proxy vote rather than the board of directors. Whether arm’s-length shareholders would know enough to do so is debatable. But the change would reduce the risk of the CFO suggesting an auditor to a committee member on the golf course.

Some critics suggest taking the selection of auditors away from companies entirely. One model would hand that responsibility to stock exchanges. However, exchanges might be more interested in using lax audit rules to induce companies to list than in courting investors by marketing themselves as fraud-free platforms. To avoid that risk, many pundits suggest that government should appoint auditors instead—or even that the profession should be nationalised. “Do people panic when the IRS descends on them, or when your friendly neighbourhood auditor that you pay does?” asks Prem Sikka of the University of Essex. “Companies should be directly audited by an arm of the regulator.” Small-government types hate either prospect.

The most elegant solution comes from Joshua Ronen, a professor at New York University. He suggests “financial statements insurance”, in which firms would buy coverage to protect shareholders against losses from accounting errors, and insurers would then hire auditors to assess the odds of a mis-statement. The proposal neatly aligns the incentives of auditors and shareholders—an insurer would probably offer generous bonuses for discovering fraud. Unfortunately, no insurer has offered such coverage voluntarily. New regulation may be needed to encourage it.

Finally, the answer for free-market purists is to scrap the legal requirement for audits. Today accountants enjoy a captive market, and maximise profits by doing the job as cheaply as possible. If clients were no longer forced to buy audits, those rents would disappear. In order to stay in business, the Big Four would then have to devise a new type of audit that investors actually found useful. This approach would probably yield detailed reports designed with shareholders’ interests in mind. But it would also allow hucksters to peddle unaudited penny stocks to gullible investors. Whether government should protect people from bad decisions is a question with implications far beyond accounting.

Dec 13th 2014 – Accounting scandals – The dozy watchdogs – http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21635978-some-13-years-after-enron-auditors-still-cant-stop-managers-cooking-books-time-some

“Massaging” figures (used to be called fiddling) is not by any means confined to financial affairs. Happens in politics all the time without most of the public even aware.

Examples : Calculating unemployment statistics; announcing the Gross Domestic Product as if it is an indicator of the actual state of citizens’ daily lives and where the country is heading.

And we all know how even a President was elected by blatant fiddling.

I’ve been exploring for a bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts in this sort of house .Exploring in Yahoo I finally stumbled upon this site. Reading this information So i’m satisfied to express that I have a very excellent uncanny feeling I came upon just what I needed. I most indisputably will make certain to not omit this web site and provide it a look regularly.

_______________

Caramen, thank you. I like you to share your views with us here. We are on a journey to find out the truth. We will probably never find the answer to the question, what is truth. This issue has plagued philosophers since time immemorial. But it is worth the journey. –Din Merican

The most “elegant” solution to the audit problem is that practised by the US Federal Reserve. In its entire history there has never been an official audit.

Pingback: tepreaksmey